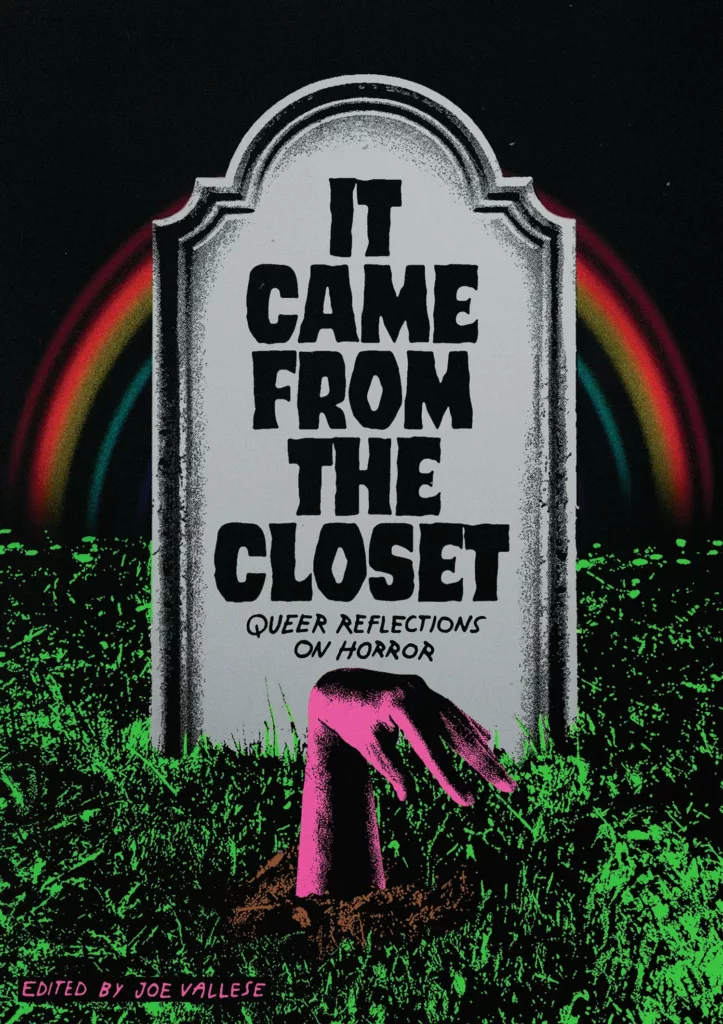

I ARRIVED AT the anthology It Came from the Closet as I imagine many other queer horror fans will: excited to see which movies would be covered, counting down until a reference was made to the “final girl,” and feeling a bit nervous about how the writers would wrestle with a genre that has historically been assaultive to the LGBTQ+ community, particularly trans women. Thankfully, editor Joe Vallese addresses these potential audience concerns in his thoughtful introduction:

. . . I and so many other queer people somehow can’t help but find immense guiltless, unironic pleasure in them. We’re titillated by the genre, even when it actively excludes us from the narrative—or, worse, includes us only to marginalize, villainize, or altogether neglect us.

My horror-fandom origin story is similar to that of many of the contributors to the collection. I started watching as a kid with my older siblings and cousins and, after encountering Scream at twelve, was forever hooked on the archetype of the final girl. Horror films always felt like a safe place to experience fear. I was in charge of how long I was afraid, as opposed to real life, where I feel a constant, underlying dread that I will be raped or murdered. I cling to the hope that the final girl will triumph.

The term final girl was coined by Carol J. Clover in her classic dissection of the horror genre and its intersection with gender, Men, Women, and Chainsaws—a work referenced implicitly and explicitly throughout the collection. The final girl herself queers horror films by bending her gender: she often has a neutral or male name, has stereotypically male interests like auto repair, and takes on an assertive investigative role once she realizes things have gone terribly wrong. When Clover wrote the book in the early nineties, she observed that horror audiences were made up almost entirely of young men. The trick of horror films is that the (male) audience begins by seeing through the eyes of the male killer as he stalks his prey but, by the end, roots for the final girl to triumph over her assailant, thereby empathizing with the female perspective.

But in It Came from the Closet, most of the contributors identify not so much with the final girl as with the monsters. S. Trimble’s high bar-setting opening essay, “A Demon-Girl’s Guide to Life” sees the 1970s possession film The Exorcist as a mirror held up to her bigoted, Christian 1990s childhood, where she discovered her queerness. She finds a kindred spirit in Regan, the possessed twelve-year-old girl, her rage and vile words butting against the Catholic church that has sent a priest to save her. Trimble recounts, “I was [. . .] becoming more attuned to the adult world and its violent separations of normal from not, saved from damned. I saw a revolting girl revolting against the little-girl box in which she was stuck—and I saw an army of men working to put her back in.” Like Prince Shakur in his essay “The Wolf in the Room” and Tosha R. Taylor in her essay “The Wolf Man’s Daughter,” Trimble relates to the maligned and often misunderstood monster as a natural response to a conservative, religious upbringing that has villainized the LGBTQ+ community.

Some of the better entries in It Came from the Closet were previously published elsewhere. Originally published in The Offing, “The Girl, The Well, The Ring” is a standout combination of film critique and personal essay. In it, Zefyr Lisowski processes her long-term illness through the lens of The Ring, a movie that punishes a young child for her sickness. Further still, Lisowski sees echoes of her transition in The Ring’s villain, the othered Samara, who is no more evil than a neglected little girl. Lisowski reclaims this narrative out of ableist hands and forces us to confront why these stories show, “[o]n one side, the heroes, able-bodied and quivering at becoming different. On the other, disabled people, shunned and cast away by dominant systems of support.” Hers was the best example of using a piece of media as a jumping-off point for critiquing larger systems of oppression.

In “The Healed Body,” Jude Ellison S. Doyle looks at the body horror genre, particularly the 2002 French film Dans ma peau (In My Skin) and how it relates to body dysmorphia. Doyle considers the genre to be “deeply rooted in cis men’s fear of femininity, and [it] considers cis female bodies to be inherently freakish. . . . This is how horror is used by the dominant culture: to justify fear and violence toward the Other, the Alien, the Mutant.” But she takes comfort in the film, whose protagonist self-mutilates in escalating ways: “There is a difference between feeling uncomfortable with your own body and having others proclaim how uncomfortable they are with you, between the horror felt by a person and the horror caused by a monster.”

I suspect many readers will pick up the book because they’ll see Carmen Maria Machado’s name mentioned in the back cover copy. They won’t be disappointed by her essay, “Both Ways,” about the bisexual classic Jennifer’s Body. In it, Machado comes for the misogynist critiques and sexist marketing campaign that initially derailed the movie from being taken seriously. She also responds to the moviegoers who accuse the movie of queerbaiting, arguing its bisexual subtext was always intentional and reclaiming the movie for the queer horror cannon. “Bisexuality itself is inherently resistant to heteronormative frameworks,” Machado writes, “because gatekeeping is shortsighted and unbecoming; because desire and understanding do not always go hand in hand.”

Horror films always felt like a safe place to experience fear. I was in charge of how long I was afraid, as opposed to real life …

Although Lisowski, Doyle, and Machado’s essays move smoothly from film analysis to extended metaphor, other entries in the anthology lack such seamlessness. A problem with any anthology which calls for submissions is that some pieces will fit the theme more naturally than others. Some essays feel like they were reverse-engineered particularly for the collection, that they wouldn’t otherwise have a reason to, say, compare a ghost story to the experience of being closeted.

I went into my reading mistakenly thinking It Came from the Closet would feature more history and analysis of the genre, like Feminist Press’s entertaining and informative anthology The Feminist Porn Book: The Politics of Producing Pleasure. Bringing together scholars, filmmakers, actors, and critics, that collection looked at all sides of the porn genre and reclaimed much of it through a sex-positive point of view. In It Came from the Closet, I found myself preferring the critical essays to the memoiristic narratives. But I can’t blame these writers for taking horror movies so personally. When you love a genre that many people find inferior, you become defensive of the dark, weird thing that nonetheless brings you contentment. Vallese writes in the introduction:

I eventually came to understand that, while I was busy fretting over whether being gay would displace me from connecting with the films I loved most, queer affection for horror was actively being claimed, recontextualized, and integrated into the culture and community—and, like most things touched by queerness, horror becomes more textured, more nuanced, and far more exciting when viewed through a queer lens.

The horror genre continues to become queerer and more inclusive—and better for it. That doesn’t erase its problematic legacy, but it does give queer horror fans hope. Instead of feeling like monsters, we can be the heroes, the survivors, the final girls. We can take charge of our fears.