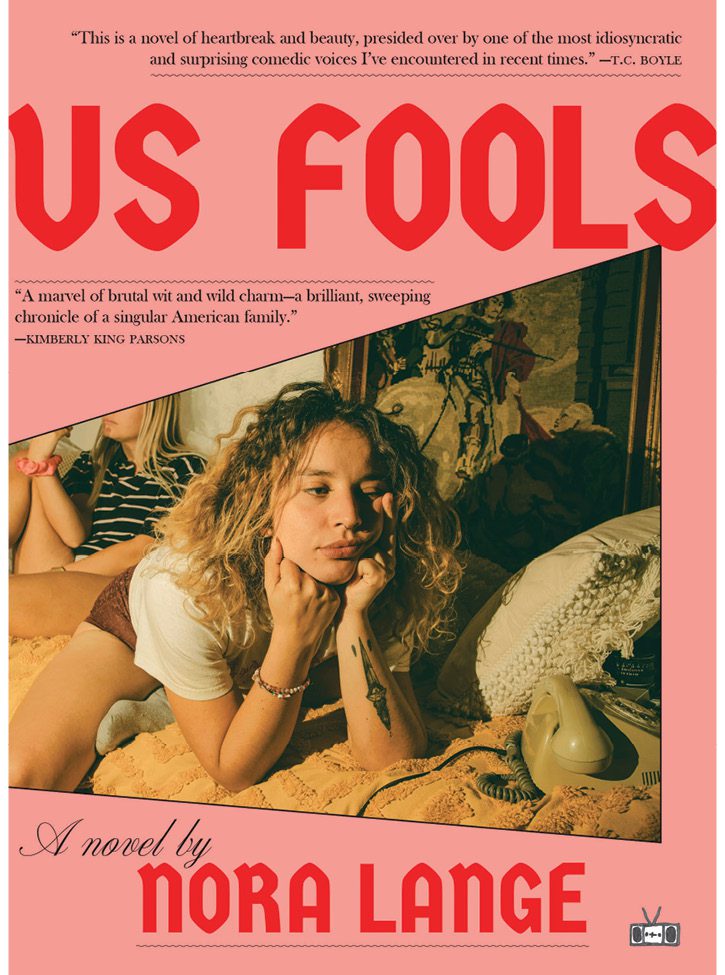

One of the formative literary undertakings of my life was reading Lynda Barry’s Cruddy at sixteen. My mother bought it from a Goodwill, delighted by the striking ugliness of the cover, and then promptly abandoned it, telling me one morning at breakfast, “Just the most terrible situation you can imagine—that’s what this book is about.” Ever the grit-hungry sleaze, I offered to take it off her hands. What I found when I pored through those pages was a relentless tragedy about a teen girl named Roberta Rohbeson, forced on a murderous road trip across America by her abusive father, an emergent serial killer—certainly the most terrible situation I could imagine. Cruddy broadened my horizon, showed me the furthest extent of what literature could be, all the filth and grime and terror it could entail. But it also showed me tenderness, beauty, America according to a snarky, idiosyncratic adolescent. I haven’t had a reading experience quite like it—that is, until reading Us Fools by Nora Lange.

Us Fools is Lange’s debut novel (don’t confuse her with Argentine avant-garde writer Norah Lange; Nora Lange is an American), yet it reads like the singular work of an acclaimed novelist. The book follows the Fareown family: father Henry, mother Sylvia, elder sister Joanne (Jo), and younger sister Bernadette (Bernie), who live in poverty on a rural Illinois farm. Bernie is our narrator, and much of the book hangs on her relationship with Jo. The two sisters have an intriguing dynamic. It’s often a Socratic dialogue, Jo waxing poetic about politics and metaphysics and what-have-you as Bernie clings to her every word. Because Henry and Sylvia are generally consumed by each other and consumed by the farm crisis of the 1980s when not, Jo and Bernie spend most of their time together without supervision, fixating on Greek mythology, philosophy, and other historical obscurities, such as the story of Martha, the last living carrier pigeon. The girls absorb their parents’ anti-capitalist, vaguely anarchist ideology and a general disdain for the country they feel has abandoned them; once, Jo declares to Bernie, “If the entire population believed their clothing came from a huge Communist country as far away as the Soviet Union, a large swath of the public would go nude.”

An important note: Jo does not speak like a normal person. Jo is not a normal person. Lange writes of her behavior in school and elsewhere:

Jo often got herself detention, or worse, suspension for her bodystink screaming:

“The body secretes. The body sweats, shits, and bleeds!” Jo liked to scream in public, pointing in the direction of France and to excessively relaxed, comfortable French women with bushy, drippy armpits lounging nude in the Riviera eating cheeses made goopy by the heat.

The evidence is overwhelming that she is yet another madwoman in a long line of Fareown madwomen. Bernie explains the family legend as “the story told, obviously, was that in time each maladjusted Fareown woman—with the help of her abhorrent sisters and equally abhorrent daughters—had removed each and every perfect baby boy that had (inevitably) been born,” thus producing a family comprised of deranged females, as well as the occasional husband tacked on for reproductive purposes. This prediction hangs over Bernie’s head as she attempts to escape the clutches of the Midwest and to develop an identity distinct from Jo. For a while, Bernie succeeds. While Jo is a dropout living with her middle-aged lover back home, Bernie goes to college. Her postgraduate life in Chicago is glamorous, busy, artistic. Though she works in the artsy humanities as a theater teacher and a poet’s assistant, Jo’s influence looms: “My students said I talked like a crackhead living in a past century,” Bernie admits. The further she tries to move from Jo, the more intensely she is pulled back. She reflects, “That twisty cord that connected us and made us less alien to ourselves was a lifeline.”

The connection between Jo and Bernie transcends state boundaries, carrying them from their rural hometown to Chicago to, eventually, a trailer park in Deadhorse, Alaska. Lange frames the chronology of this journey as an ode to America, upon which the sisters reflect constantly. What is America? What does it mean to be an American? Sylvia claims that “the very act of living in America had excluded grace.” Fais, a girl with whom Bernie has a brief romance, is complimented to the highest degree when she is referred to as “kind and American.” Bernie even paraphrases Freud, who, after visiting Coney Island, “called our country a gigantic mistake”—an assessment she finds “ominous yet vindicating.” In an honest tribute to the States, of course, one must be critical. The Fareowns’ American Dream is a farce, dead in the water, perhaps the buried cause of the family’s genetic insanity. Their life is one of Midwestern deprivation, which Jo succinctly summates: “Our parents are miserable adults who will never see the ocean.”

Yet, with their insular connection, Jo and Bernie morph their Americanness into something new, a kind of atheistic folk religion practiced by them and them alone. As a duo, they refer to themselves as “junk kids.” At times, it seems like a cult of two. Other times, it seems like a case of folie à deux. The sisters lay out feasts for themselves, let the food grow moldy, then “eat the rotten matter and get sick just like true worshippers of religion.” Without a doubt, in their nameless faith, Jo is high priestess. Lange writes, “I studied her like I was memorizing a church verse. I studied her because she looked like our mother, who looked like her mother.”

This kind of mysticism is altogether absent from Cruddy, so why is it that Us Fools reminds me so much of Barry’s novel? It doesn’t have the same stink, nor does it contain violence on a similar scale. However, both books are portrayals of the pitfalls experienced by young people navigating the most sordid parts of our society, propelled by writing that finds beauty and humor in the freakish failed experiment that is America. These dreary, Gummo-esque depictions of youth (in which kids huff glue while pondering the philosophical complexity of mortality) typically feature male protagonists, a masculine home for all the dirt and blood and “junk” of adolescence. But Roberta and the Fareown sisters are juvenile dialecticians with middle-of-nowhere disillusionment and trailer-trashy bents, and their gender produces more commentary on the status of American womanhood than possible in your run-of-the-mill, Harmony Korine–style story. Just as Roberta’s father, in his misogynistic, murder-induced mania, tries to earn her good graces by telling her, “You ain’t even female to me,” Bernie tells us that she “came to understand that from the time my sister could speak, her language, behavior, and the hormonal shifts that would later follow were being weaponized against her. Against us all, really.” Later, she theorizes, “From birth, ‘woman’ was defined as ‘tool,’ and a tool was an object man used for violence, in other words: women were the initial enemy of men. And since man was God, it could be said that women were the initial enemy of God.” Roberta, Bernie, and Jo scrape at the edges of their genders. They push against the margins. They are bizarre, they are bitter, they are American, and they are girls.

I think of Roberta as a “junk kid.” She doesn’t grow up naturally; she is made an adult by good, old-fashioned man-made American suffering “on a cruddy street on the side of a cruddy hill in the cruddiest part of a crudded-out town in a cruddy state, country.” As Jo pontificates, “We are surrounded by America with its orgies of barbarism.” As Bernie recapitulates, “America was all I knew.” I finished Us Fools like I finished Cruddy: eyes open, staring out at the country I was born in, feeling that something had changed, that some loveliness had emerged from all the muck and filth and crud. Quoth Bernie as she looks at “industrialized parks and motorized vehicles and signs of nature in the distance”: “America could be beautiful.”