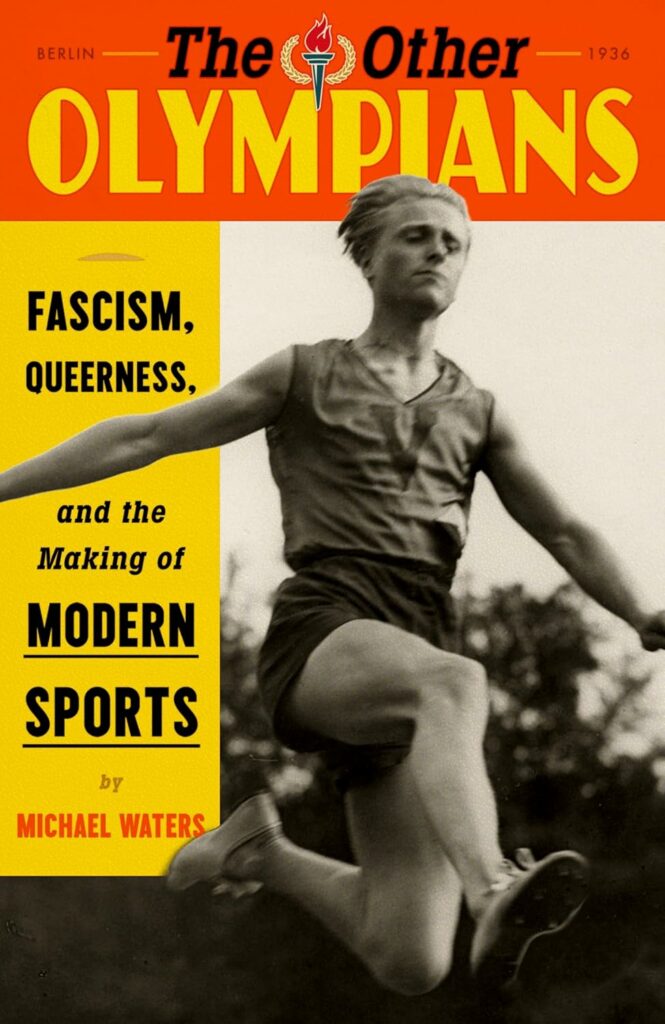

It’s funny that the first question from many people, when they hear a positive stance on transness, is “But what do you think about transgender people in women’s sports?” As if these interlocutors had any stake in women’s sports to begin with. As if the most pressing issue facing trans people today is athletic events. And as if keeping trans athletes out of competition is sacred, noble, the last bastion of women’s rights. In fact, these contemporary trans-illiterati have a long lineage. Their antecedents were unknown to me until I read Michael Waters’s fascinating history, The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, which reveals this line of questioning to have deeper and darker roots than I would have guessed. Waters’s research shows that athletic sex testing as we currently know it was created for the 1936 Olympics in Berlin by the Nazi regime.

The goals of sex testing, then as now, are “murky,” Waters writes, and undeniably complex. To understand the reasoning behind the intense (and, more often than not, subjective) separation of the sexes that continues to haunt us in the present tense, one must first understand “the specific conflagration of Nazi ideology, 1930s understandings of sex, and the ambitious personalities of men . . . that ushered these policies into existence.” One must also understand the history of the two athletes whose transitions inspired the entire fiasco: Zdeněk Koubek and Mark Weston.

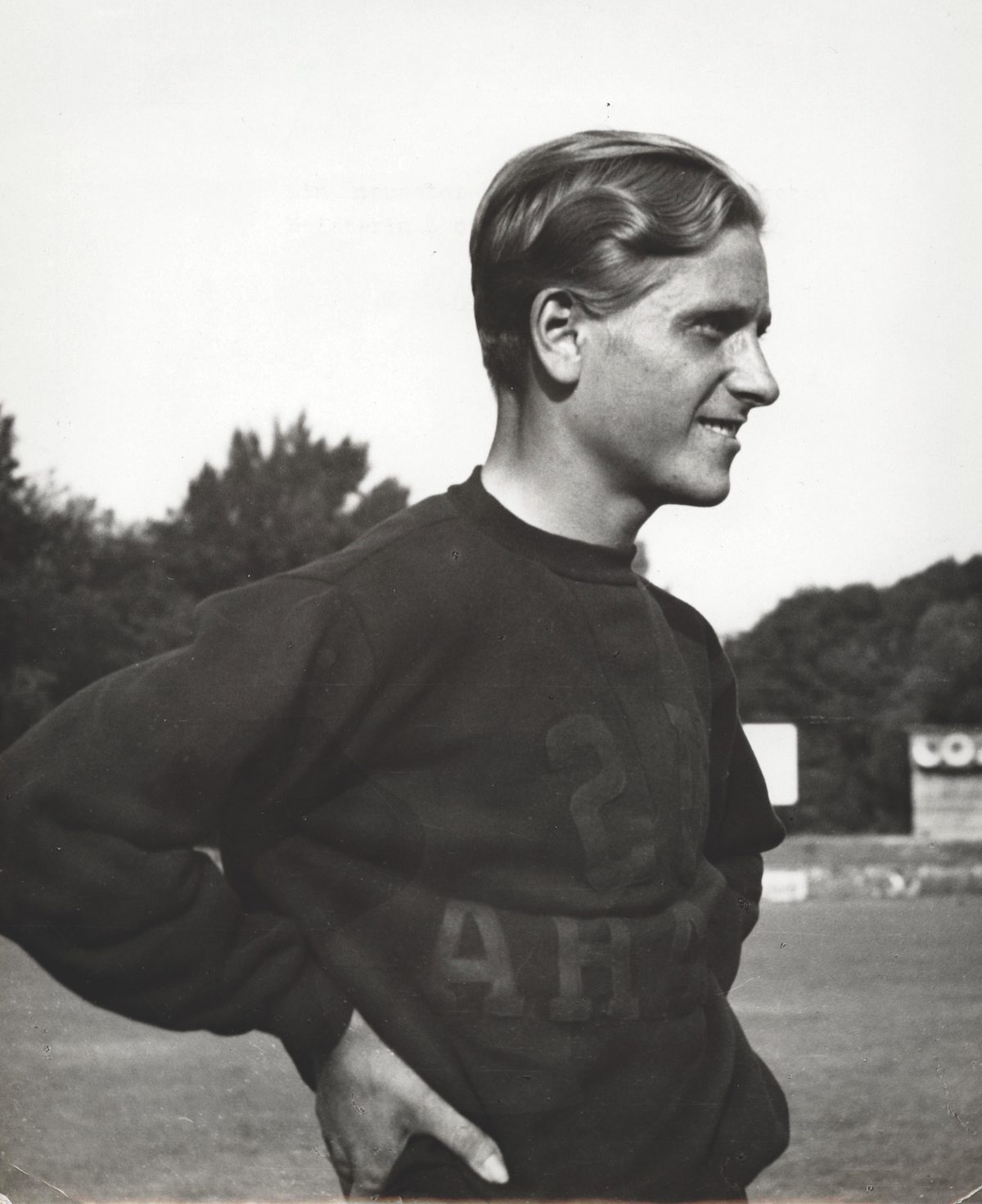

Using contemporaneous news articles, histories, and autobiographical essays, Waters elegantly pieces together the life story of the runner Zdeněk Koubek, whose birthplace, Austria-Hungary, was violently transformed into Czechoslovakia when he was five years old. Koubek had, unsurprisingly, a tumultuous youth, facing ridicule for his boyish mien, the backbreaking pressure of early twentieth-century gender roles, and failed romantic relationships with men so overwhelming that one bad date drove him to blurt, at its end, “Listen to me, I’m not a girl at all.”

“The older Koubek became,” Waters writes, “the more peculiar he found the rituals of femininity.” Women’s athletics, however, proved a theater for Koubek’s early self-expression. At the time, European women’s sports were spearheaded by a Frenchwoman named Alice Milliat, who, after founding France’s first women’s sports league (the Fédération des sociétés féminines sportives de France), went on to form a massively popular international league for women’s sports called the Fédération Sportive Féminine Internationale. In 1922, she “held the first Women’s World Games in Paris,” an event boasting seventy-seven athletes and around twenty thousand attendees. Milliat, in spite of all of her defense of “the weaker sex,” “was no radical.” Waters writes, “She could often be heard touting the femininity of her athletes to reporters. She wasn’t trying to blow up the sporting apparatus—she just wanted to carve out space within it.”

Still, gender-nonconforming athletes like Koubek were attracted to the freedom that women’s sports offered. Koubek attended the 1934 Women’s World Games, where he won gold “in astonishingly quick time.” His gender expression caused a bit of upset in the press, however. Canadian coach Alexandrine Gibb commented that “it wasn’t so amusing, not when you were there and saw real feminine Canadian girls forced to compete against that sort of mannish athlete in track and field events.” At first, Koubek brushed off the comments. Eventually, though, he decided he “needed to reckon with” his gender and retired, undergoing several surgeries (the medical details of which he kept private) and publicly transitioned to a man—even doing interviews and going on a press tour to allow the fascinated masses their chance to peek behind the veil of gender.

Photograph by Agence Rol / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

“Women who participated in ‘masculine’ sports like soccer or track and field risked creating a third category of sex.”By the 1936 Berlin Olympics—which, by then, had absorbed the Women’s World Games (the accomplishments of women never permitted to stray too far from the paternal control of male officials)—Koubek had arrived at “that dreamt-of place—the other shore.” He left women’s track and field behind and pursued men’s club sports. He didn’t attend the 1936 Games, nor did the other athlete Waters profiles, English shot-putter Mark Weston. Despite his geographical distance from Koubek’s Czechoslovakia, Weston was inspired by Koubek. Closely following the media frenzy amid the incredible revelation that “the boundaries of sex were permeable,” Weston medically transitioned as well. Faced with two semi-famed women’s athletes transitioning within a relatively short period of time, the general public was in an uproar. After all, this was a public that believed that, as Waters paraphrases the British paper the Daily Herald, “women who participated in ‘masculine’ sports like soccer or track and field risked creating a third category of sex.”

“Women who participated in ‘masculine’ sports like soccer or track and field risked creating a third category of sex.”

Also shaken by Koubek’s and Weston’s apparent transformations (which some befuddled scholars posited could be catalyzed by “outside forces, like disease or physical exertion”) were the International Olympic Committee and the Nazi Party. The ensuing hysteria compounded fears over some masculine-presenting female athletes attending the Games and influenced a fateful decision. Wilhelm Knoll, the Nazi sports doctor who first proposed sex testing, declared in a letter to the International Amateur Athletic Federation, “I request that all female participants in the Olympic Games should have their gender checked beforehand by a specially-commissioned doctor.” Waters argues that such gender-checking was not just humiliating; it was prejudiced, misguided, complex, and arbitrary:

Would he have considered a woman with too much muscle or body hair to be “abnormal,” and at an advantage, and therefore worth disqualifying on the grounds of cheating? What about tall women? Didn’t they have an advantage in some sports, too? Or was he simply concerned with genitalia—and if he was, what genitalia would he have considered disqualifying?

When implemented, the gender examinations were, of course, anything but scientific. Helen Stephens, a five-foot-eleven cisgender lesbian from Missouri, was singled out and subjected to an invasive sex test. In subsequent Olympic Games, muscular female athletes such as Soviet track and field star sisters Tamara and Irina Press were targeted. When the Press sisters declined to undergo testing, their gender identities were publicly scrutinized: was their discomfort with the procedure an expression of guilt, the media wondered? Absurd accusations that men were masquerading as women to best them in sports flew through the press. “What happens?” asked one London newspaper, before offering a personal theory: “A big boy in his teens may show all the signs of being a good hammer-thrower or shot-putter. So in some countries they don’t hesitate to feed him on female hormones.”

Koubek and Weston, despite having inadvertently fanned the hysteria, faded into friendly obscurity. By the time of their deaths—in 1986 and 1978, respectively—they had long been accepted in their communities as men, the transphobic-slash-misogynistic-slash-transmisogynistic mania and sordid politicking of international sports behind them.

The Other Olympians is not a neutral text, nor should it be. Waters exposes decades upon decades of oppression and repression and pure, vitriolic hatred for a minority group that, even today, is despised, maligned, and profoundly misunderstood— in the athletic sphere, and in daily life. In such a clear-eyed account, there is no room for alternative interpretation: this is trans history, trans fact. Though Waters’s chronicle is information-dense, his prose is stylish and narrative, making The Other Olympians a welcome and necessary addition to the queer canon.

The Other Olympians is vital reading in this era, in which gender-musing is scoffed at as anti-scientific drivel or a self-obsessed generation’s yearning to be different. I was delighted to read that ideas about the “permeability” of gender long predate the current debate. Waters makes sure to show that in the twentieth century, as now, there were experts and ordinary folks who supported trans rights. He quotes a 1936 remark by American sexologist Donald Furthman Wickets: “Sex is relative. No man is 100 percent male, no woman 100 percent female. Every male, even the lustiest, retains certain rudimentary characteristics of the other sex.”