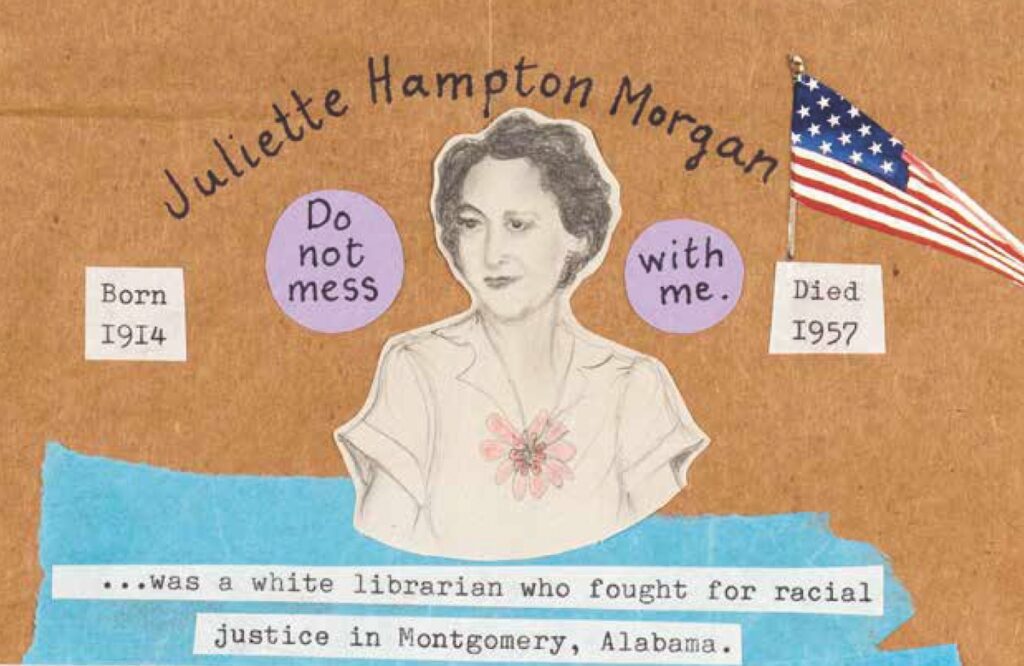

Librarians feature prominently in my two most “controversial” books for children. In Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness, a white child visits the library with their mom and learns from a library book about the history of systemic racism in the United States and the legacy of white people who aligned with black leaders and liberation all along. Not My Idea encourages white children to tune into their instincts about racial justice and step into that legacy by acting from their own desire to be free from a system they never consented to uphold. As an example, I included a tribute to a white librarian in Montgomery, Alabama named Juliette Hampton Morgan (1914–1957). Morgan was from a wealthy white family in the Jim Crow South. At that time, it was common for white bus drivers to collect bus fare from black riders, then drive off and leave them when they stepped off to re-enter the bus at the back. A frequent bus rider, Morgan became known for pulling the emergency cord anytime this theft and abuse happened on her watch. She raised hell on those buses to force the driver to do his job. I describe her choice in the book as “an act of love, for herself and the community to which she belonged.”

In my middle-grade book What You Don’t Know: A Story of Liberated Childhood, my protagonist—a child who is black, white, embraced by their family, and openly identifies as queer—tells readers about the few adults at his middle school who look out for him and try to provide a safe space. Among them is “Addie, the radical librarian”—tattooed, pierced, and white—who tells him, “If I don’t have what you need, I’ll find it.” Her words hold enormous power; she is not only helpful but courageous, as in, willing to confront fear, difficulty, and danger so that this particular child can receive the resources he needs. Just as it took real nerve—plus the conditional safety of belonging within whiteness—for Morgan to cause a ruckus on a bus full of people from different positions of entitlement and exclusion, the librarian in What You Don’t Know takes a risk when she vows to provide what a child is seeking. This is an act of love, for herself and the community to which she belongs. There are consequences to a love like this.

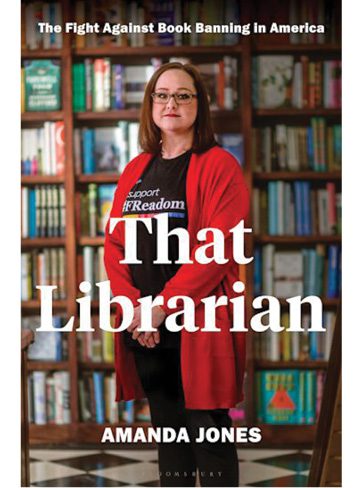

Librarian Amanda Jones documents such consequences in painstaking detail in That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America. Her trouble began at a local public library board meeting on July 19, 2022 in the small town of Watson, Louisiana, where Jones was born and had spent her whole life. Jones was not the only person at that meeting reminding people that public libraries are funded by everyone and are for everyone, and that librarians can and must be trusted to maintain a safe, educational space. “I said nothing earth shattering,” she recounts, but the earth shattered.

Jones was accused after that meeting of providing “sexually erotic and pornographic material to six-year-olds.” At the time, her awards and distinctions included 2021 School Library Journal Co-librarian of the Year, 2021 Library Journal Mover & Shaker, and 2020 Louisiana School Librarian of the Year. The attack on Jones began with two Facebook posts, shared hundreds of times—one from Michael Lunsford, Executive Director of Citizens for a New Louisiana, the other from Ryan Thames, a local man who moderated their town’s “Facebook rants page,” which had 43,000 members at the time. These two white men put Jones in their sights and spun things way, way out of control. The memes, the doxxing, the twisted lies and teasing—Jones refreshed her screen again, and then again, as the attacks on her character grew exponentially and got meaner and more personal.

What drew this ugly attention? Simply this: by promoting free speech and urging her community to rely on well-trained librarians and library policies already in place for vetting, choosing, and challenging materials, Jones aligned with the targeted books about race and sexuality, and the targeted people, the black and brown and LGBTQ+ authors, characters, and human beings these groups want to ban from existence. That alignment made her fair game for hatred of biblical proportions, and for an old American tradition: the violent, white mob.

For the record, Jones also avows Christian values rooted in her faith, and shares openly in the book about her personal evolution in regard to race, gender, and sexuality. Her experiences of being publicly vilified, ridiculed, threatened with murder, and litigated against by people she thought she knew and some of whom she liked—people who claim to care about children—challenged everything she thought she understood about fairness and justice, and she learned where she stood.

Before Not My Idea went to print, I asked a trusted advisor in my work, Reverend angel Kyodo williams, to take a look. Rev. angel is a Zen priest, author of books about black grace, healing, and liberation, and a spiritual guide through these and, really, any times. I brought my binder of original collages and she studied each page, offering valuable suggestions. Then she said, “You haven’t yet prepared your reader for the rejection they will face in their families and communities the moment they start speaking up about white supremacy.”

I took this in—for the book and myself—and revised. For this reason, the story of Not My Idea ends with the child alone, reckoning with one piece of history that hasn’t been written yet—their own. Will they align their sense of justice with their actions? The activity pages that follow steer readers of any age toward a simpler framing of a white supremacy than the one that calls it too painful and difficult for (white) children to comprehend (and thus protects white supremacy by preventing us from questioning it). “White supremacy is pretend,” I wrote, “but the consequences are real.”

Image courtesy of Dottir Press, 2018.

While I am interested in the excruciating details of Jones’s legal battles and daily mistreatment online and in real life, what really got my heart pounding was how it affected her health. Terrified and terrorized by the online bullying, scathing lies, and threats to her life, Jones’s mental and physical health deteriorated fast. At times, she couldn’t move. She couldn’t work. Her hair fell out. She needed medication. Her legal representation cost a fortune. She was betrayed by damn near the whole town, despite having taught most of the children of the people tormenting her, and, in some instances, her tormentors themselves. Throughout the ordeal, she was held by her husband, sisters, parents, grandmother, a few close friends, and a teenage daughter who was very, very proud of her. Yes, she wept rivers and suffered panic attacks, but she also got care, got stronger, and dared to keep fighting for public libraries, librarians, and free speech. Guided by her own training and professionalism as a 21-year veteran, a front-line, award-winning school librarian and middle school teacher, Jones mostly went high when they went low, using the legal system. She filed a defamation of character lawsuit to protect herself from further harm. Even with excellent representation by attorneys experienced in First Amendment law, she lost and lost and lost in her case against those who lied about and continued to endanger her.

Here is what she won: she learned she was not fighting alone.

As bad as it felt and as costly as it was to be cast out of polite society for siding with the other outcasts, Jones found herself in the company of those she admired most of all—her fellow librarians from all over the country who were also dealing with threats and intimidation, as well as some of her favorite authors. “I was in awe that they even knew who I was,” she writes. Kwame Alexander made a video with her at her public library; she received personal messages from Nikki Grimes and then met her at an ALA Conference; she had dinner with Ellen Oh, saw Judy Blume speak in person, and met ALA executive director Tracie D. Hall and Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden. New friends also included folks from women’s and LGBTQ+ groups who’d long been fighting these battles, such as 10,000 Women Louisiana, Louisiana Trans Advocates, and Louisiana Citizens Against Censorship. They showed her how to dust herself off and keep going, courageous and capable beyond what she previously believed possible.

The part of Juliette Hampton Morgan’s story that I do not share with children in Not My Idea is how she died. A PBS mini-documentary online quotes Morgan as having said, “Faith is life lived in the scorn of consequences.” And Morgan faced that scorn head-on, until it became too much.

After her direct actions on Montgomery’s buses, word spread. Soon, Morgan was getting kicked off of buses by drivers and ridiculed by white passengers as she exited and walked to her destination. After she wrote to the local newspaper in support of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, she endured harassing phone calls and bullying by neighbors and strangers. After the mayor of the town called for her to be fired from her library job, she agreed—as a condition of her employment—to stop writing letters to the local paper. After she wrote letters to the papers anyway and members of her community burned a cross on her front lawn, after her mother complained she was disgracing the family name, Morgan resigned from her position as director of research at Carnegie Library of Montgomery and swallowed enough pills to end her life.

Here is what she won: she learned she was not fighting alone.

To paraphrase Loretta J. Ross, the author, educator, and speaker who helped create the reproductive justice framework, co-created SisterSong, and models how to call in rather than cancel out one another: “In times like these, it’s important to remember there have always been times like these.”

This past January, I presented at the American Library Association Conference in Baltimore, Maryland. Speaking engagements can be humbling; there might be two people, one of whom is you. Fourteen librarians had registered to take part in my workshop, called “How to Talk to Children About Tough Topics Without Causing a Controversy.” As if I know. I really don’t, but just like the librarians I looked forward to meeting at ALA, I try in earnest, artful, and disciplined ways to keep the focus on what’s most important: being present, listening, setting clear and kind boundaries, and letting kids lead. The night before the workshop, I stayed up till 2 AM, carefully constructing collage kits for the librarians who’d signed up. I made four extra kits, just in case. My slide deck showed images from the books and behind the scenes, paper doll adult characters who were warm, boundaried, attuned, and accountable to children. My goal was to keep returning to the ideas of genuine presence, curiosity, and letting a child see you care about what they care about—even when you can’t solve the problem or save them from trouble, even when you can’t say certain words for fear of incurring the wrath of a few parents, followed by a mob. What can you say? Can that be enough?

In the morning, I stopped by the keynote event and listened to the panel of librarians on stage describe how much they do with their communities that has nothing to do with books. They help people fill out paperwork to access social services and file their tax returns; support English language learners; offer free Wi-Fi, computers, and printers to those with no “home office.” They provide a safe place for tweens and teenagers to gather and get help with assignments. One panelist shared through tears how it feels to provide sandwiches, fruit, and snacks to a child on a Saturday, knowing this might be the only real food they eat until the library reopens on Monday, thanks to the deliberate defunding of libraries in cities across America. Meanwhile, local police departments—I can’t even finish that sentence.

Afterwards, I proceeded to the conference room assigned to me. It was huge, which was a bummer; a big room makes twelve people feel like two. Someone met me to make sure the projector and microphone worked perfectly, and then the people trickled in. A few, and a few more, and then a lot more. Way more than the eighteen I had prepared for. By the time the workshop began, there may have been sixty librarians in the room, smiling toward me. Those with collage kits in front of them popped the lids off their glue sticks like the old pros they were and began arranging pre-cut images of skies, trees, sidewalks, stoplights, houses, cats, and birds onto the square, grocery bag paper backgrounds I’d provided. People kept arriving. I lost count.

I opened every box of supplies I’d brought and invited folks to come up and take what they wanted, all the paper and collage images, the snips of ribbon and pre-cut paper dolls, but asked them to please share the glue sticks and scissors, because I didn’t bring enough. Some helped themselves and made collages while I talked, others simply listened, asked beautiful questions, and shared their own strategies for managing kids’ disclosures about their lives and need for support that goes well beyond books, though a lot can happen with just books.

On the drive back to NYC, I marveled at my miscalculation and at the opportunity to speak to and hear from so many library professionals about something that mattered to all of us: Can we be there for kids with things being exactly as they are, not trying to fix or avoid what’s true for them—or for us? How much are we willing to risk in order to resource them in all the ways?

Cornel West says, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” Surely the corollary to this is the angry mob, whose choices and voices have real consequences, even when they blast hate through screens in the name of the god of their understanding. In an August 2023 NPR report about Jones’s experience, she shares that about a dozen former students of hers who identified as LGBTQ have died by suicide. The piece quotes Jones: “I just think I have a responsibility to speak out. . . . So when they want me to be quiet, I always say, ‘I’m going to roar. I’m not going to stop.’”

That Librarian is a book about finding those who will stay with you when shit goes down, which is what everything needs to be about right now. Keep flipping the focus: we’re not fighting against those who want to bury the truth along with the bodies of those who speak it. We’re fighting in solidarity to love what we love and how we love, together and aware of the consequences, keeping our focus on how well we treat ourselves, each other, and Earth as the source of the life in all our own bodies.