The other day, while walking down my driveway to get in my car, I noticed what looked like an enormous tangle of grape jellyfish: my bloody tampons, littered all over the street, spilling out of our garbage cans. Someone had rifled through our bins, looking for recyclables or whatever, and instead found bags of bloody tampons, which they decided to fling into the air like biological confetti. I started to shovel the purplish stumps back into the bins with my bare hands, embarrassed to have my gynecological Armageddon playing in front of my neighbors, and fascinated by the sheer quantity of them. I really have been bleeding my brains out—no wonder I feel so tired and crazy.

Later, my husband took my three kids to a death-trap waterpark in Los Angeles. I didn’t go because we all knew my freewheeling anxiety would ruin the experience for everyone, and, as noted, my 49-year-old broken uterus has been bleeding in an endless loop for months and so I am banned from cute water sports. My eldest, my puffling Sigrid, just graduated from high school, and I cry every day, pre-grieving the end of young motherhood, that exhausting job I have felt ambivalent about for the last seventeen years. I smother her and rage at my family (every day: approximately 4:30 PM) and change a string of never-ending tampons and wonder, what the fuck is going on with me? I feel like an insect trapped halfway out of the chrysalis, half-worm/half-winged. I haven’t been this bloody and unhinged since I was thirteen. Or postpartum.

The main character of Sandwich, 54-year-old Rocky, is going through a similar metamorphosis. Sandwich has a line about something being “a wolf in clown’s clothing,” which is an apt description for this book—it’s a funny, readable story about love and family and agreeable clam shack dinners, but in between, it digs up the bloody parts of being a woman and mother.

The novel follows Rocky’s family during their annual week on Cape Cod—affable husband Nick, grown-up kids Jamie and Willa, Jamie’s girlfriend Maya, and Rocky’s elderly parents. Rocky is me and my sisters and every one of my friends—alternately joyful, forgetful, and enraged. She loves her husband but also thinks he doesn’t understand anything, ever. She is bewildered by her aging body. She fears her beloved white-haired parents getting sick and dying. She is knocked back by waves of nostalgia for when her kids were small and sticky and dependent. She looks at her college-aged daughter and thinks, “Are all those little girls nested inside you like matryoshka dolls?”—capturing that disorienting flip-book feeling we get as we get older, seeing the past, present, and future spin by all at once. Or maybe it’s a different mechanism: Newman writes, “Life is a seesaw, and I am staying dead center, still and balanced: living kids on one side, living parents on the other. Nicky here with me at the fulcrum. Don’t move a muscle, I think.”

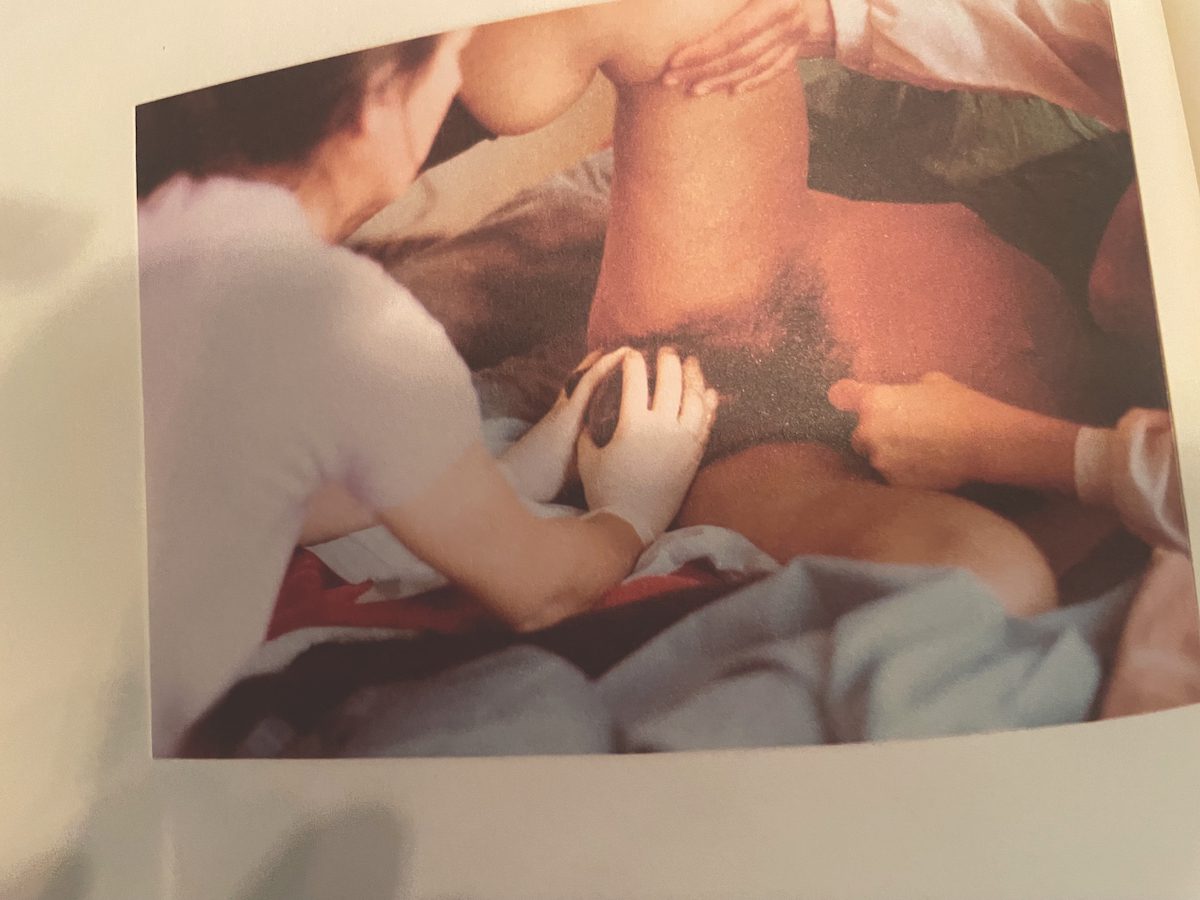

Not so much plotted as written as a series of tragicomic meditations on motherhood and menopause, the novel’s apex is Rocky’s long-ago abortion, a narrative point that seems like another way for Newman to explore how a positive pregnancy test can feel like the most lucky or impossible thing, depending on timing. Rocky ended this third pregnancy when her youngest was a baby because she was overwhelmed and frankly exhausted by loving the children she had. She took mifepristone but told her husband that she was miscarrying. She waded into the Atlantic and “bled the baby away into the brine. There were no sharks that I could see. I wanted obliteration. But also, I wanted life. I wanted to keep the life I had.” When Rocky gets pregnant again the following year and miscarries, she feels regret about the abortion. Through all of this, sex starts to feel like a dangerous game that only she is playing: “total reproductive mayhem every second. A gynecological shit show. And then I’m supposed to be excited about sex? It’s like we’re riding a Ferris wheel in a fucking cemetery!”

Through all this, sex starts to feel like a dangerous game that only she is playing.

This resonates. I’ve struggled to be sexual since my adenomyosis (broken uterus) either leaves me hemorrhaging or curled in pain—a gynecological shit show to be sure. I think most perimenopausal women feel at least a disconnect from desire. Beyond hormonal sabotage and aging bodies, sometimes I don’t understand how women are supposed to just continue fucking after everything that comes out of our vaginas. Rocky feels anger at her husband for being whole and simple and unscathed by parenthood, a metaphor for the patriarchy: “Sex is still about pleasure for him . . . not a holy act of grief-stricken joy. It is not exhibit A in a PTSD trial.” These days, when sex comes up as a possibility for me, it’s like I’m looking through a View-Master toy at a lifetime reel of images, some thorny—those times I felt pressured, those times I felt disembodied, those times I felt ugly or embarrassed. I have to force myself not to let my mind go down the rabbit hole or, God forbid, start talking about it out loud to my husband. (See Miranda July’s amazing new book about middle-aged femaleness, All Fours, where she calls this being a “mind-rooted fucker.” Upshot: not ideal for anyone involved.) Perhaps it’s hard to feel sexually embodied after so many years of being a food factory, a comfort factory, a workhorse. “When they were little there was so much [] touching. . . .What I wouldn’t have given to plant a flag on myself—to claim a single square of my own flesh.” This is the loneliness of being a mother, always surrounded and consumed by other people.

Dark sex thoughts aside, Sandwich gave me some belly laughs about the absurdity of menopause, like the inexplicable hormonal rage that “burns and unspools, as berserk and sulfuric as those black-snake fireworks from childhood; one tiny pellet, with seemingly infinite potential to create dark matter—dark matter that’s kind of like a magic serpent and kind of like a giant ash turd.” Those nights around 4:30 PM, right when I should be thinking about what to make for our 4,573rd family dinner, I feel that ash turd growing in my gut. It goes away by morning—but let’s talk about the insomnia and anxiety in the meantime! For the past year or so, I have only dreamt of packing never-ending suitcases for planes that I always miss. Rocky muses, “If I sleep at all, I dream that I’m trying to punch urgent numbers into my phone except I have stump hands.” Speaking of stump hands, what’s going on with my body? I awoke the other day to the unsettling realization that I have a straight line of blobby lipomas growing on both of my thighs, like somebody shoved a line of jumbo marshmallows under my skin with a chopstick. (Just like my Grandpa Skuli! And my mother!) Newman writes, “You are covered in weird growths, as if a toddler has gotten a sheet of mole stickers and stuck them all over your breasts and armpits.” And we must discuss the horror of middle-aged hair—I thought men had all the bad luck there, but no—it turns out hormones and iron deficiencies will also make your hair fall out until your ponytail is as thin as a child’s pinky and your scalp-y part glistens in the sun. Rocky’s hair is described as “simultaneously coarse and weightless in a way that seems like an actual paradox, as if [her] scalp is extruding a combination of twine, nothing, and fine-grit sandpaper.”

Best of all, Newman conjures a sense of place in Cape Cod with her descriptions of man-eating sharks and shrimp-smelling sand, quiet algae ponds and delicious seafood meals. I know that the title, Sandwich, is supposed to mean her metaphorical place between grown children and aging parents, but she writes a lot about literal sandwiches—like twenty percent of the book is mouth-watering descriptions of bluefish pate, dill pickle chips, and lobster dinners. Maybe once the lure of sex dims, salty snacks remain . . . thank God.

Sandwich is an optimistic menopause novel. Rocky struggles, but the reader knows she will find her way in the end, with her supportive marriage and positive relationships. I hope for the same for myself when I come up for air after sending my (now ten-year-old) youngest puffling off the proverbial cliff. Up to this point in my life, it has felt like everything I did was about adding life—more babies, more chaos. Suddenly, the seesaw tilted and I am standing on the minus side, facing a hysterectomy, an emptying nest, and the specter of my dad’s cancer reoccurring. I am ambivalent about the daily grind of motherhood ending, just like I felt ambivalent about being a stay-at-home mom in the first place. Neither place is particularly comfortable.

Maybe I should macramé my endless strings of tampons into a little safety net for myself, to catch and bounce me back onto my feet, where I can reintroduce myself to myself. In the meantime, I’m glad Sandwich and All Fours are getting the attention that they deserve, so I can feel embraced by all the other complicated harpies out there. We are legion.