Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, MA. Gift of the artist, 1995.

© June Leaf and Robert Frank Foundation.

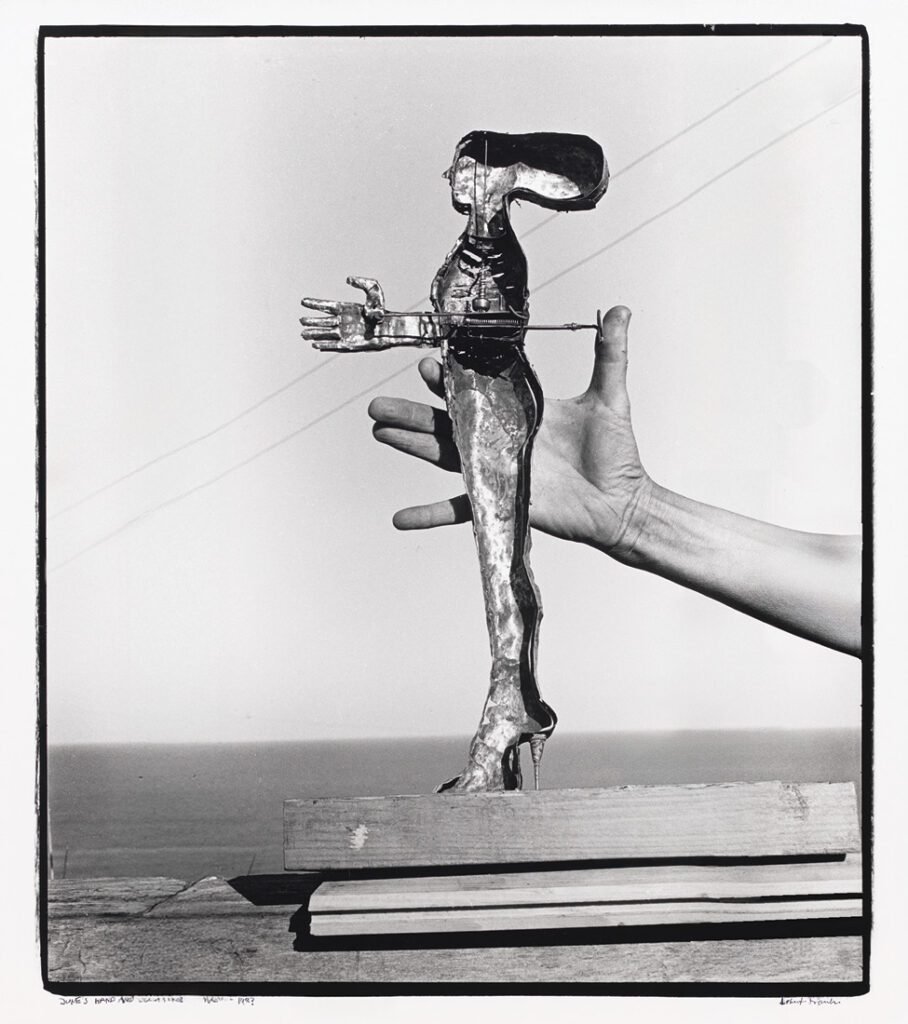

The June Leaf sculpture depicted on this issue’s cover, Shooting from the Heart (1980), lends its title to the Leaf retrospective on view at NYU’s Grey Art Museum through December 13. Photographed here is the artist’s hand by Leaf’s third husband, the Swiss American photographer and documentarian Robert Frank, the 18 × 8 inch figurine—composed of tin plates, rods, spring, and gears—appears both ancient and futuristic, both sleekly high-femme and monstrously composite. There is a hint of an Egyptian sculpture, or a Cycladic figure with an arm exaggeratedly unbound into a huge finger-gun. One sees, too, a bride of Frankenstein, a fembot, a feminized take on the creature from Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). The image of a balloon-headed woman—“pregnant with ideas” as Sam Adams writes in the catalog for the current retrospective—which recurs throughout her work in that period, came to her spontaneously, inspired by the “reflection of a buoy moored in the waters off Cape Breton.” Leaf had a mania for discerning images from random abstraction—sidewalk cracks, slides under a microscope—bringing a palpable element of the unconscious and unexpected to her prolific and protean work.

Leaf’s career is hard to classify. Words like “enigmatic” and indeed “unclassifiable” were used frequently by critics. In a New York Times review of a 1973 show, John Canaday wrote, “Miss Leaf is an exception to everything, including every specific esthetic standard ever formulated.”

Born in Chicago in 1929 to West Side Jewish tavern keepers, Leaf took weekend classes at the Art Institute and studied briefly under the Swiss painter Hugo Weber at the New Bauhaus in the 1940s. Though early influences included Paul Klee and Mark Tobey, she joined an alternative tradition of midcentury American artists who rejected the gospel of abstraction in favor of expressive figuration. In dialogue with Chicago contemporaries like Cosmo Campoli and Nancy Spero, Leaf also took formal and emotional cues from figurative European modernists like Ensor, Ernst, and Giacometti. The cartoonish idiom of her early paintings—surreal caricatures and Dionysian street and theatrical scenes—also brings to mind works by slightly junior fellow Chicago painters inspired by comic-book aesthetics, like those who formed the Hairy Who collective.

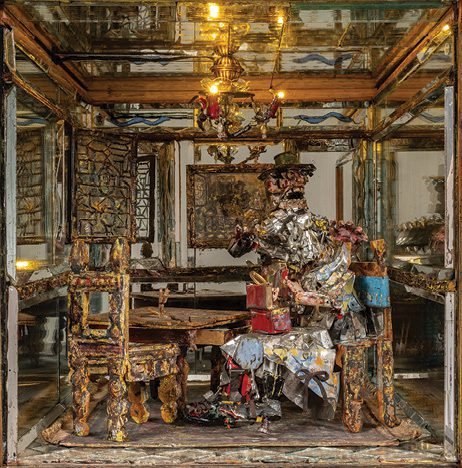

Leaf’s carnivalesque figural idiom came from the arcades, joke shops, and circuses that defined her feral, working-class childhood, but her interest in a more formalist tradition persisted. In the early 1960s, she applied herself to transcriptions of Goya and Vermeer but grew frustrated with trying to imitate their two-dimensional naturalism. “It’s not right,” she later recalled feeling. “There’s something missing. There’s a dimension that’s not here. . . . Well, if you can’t paint it, why don’t you sit down and make the lady in the room.” Thus her career as a sculptor—a practice she would use, for the rest of her life, synergistically with that of painting—began with a funhouse miniature tableau of Vermeer’s The Glass of Wine in which “a gnarled, wild-eyed man with gnashing teeth stands behind a woman with a mirrored head . . . accessing,” as Allison Kemmerer and Gordon Wilkins write in the catalog for Shooting from the Heart, “the psychodrama that is subtly suggested in Vermeer’s paintings.”

Leaf’s perennial preoccupation with gender dynamics and the female body slightly anticipated those of the feminist art movement, in which she had little interest. Per a 2023 interview in Pin-Up: “It was the time of the women’s awakening, and I was very bored by that, because I had had my awakening and then some in that time. And here comes the women’s movement pestering me. But I thought, ‘Why don’t the women just make a monument to themselves?’” Leaf never literally constructed such a monument, but for much of her career she circled around the concept, constructing striking female figures that span a visual language from cyborg to fertility figure, making studies for something she called Woman Monument—“Something so big, so powerful that it’ll shut the men up for good.”