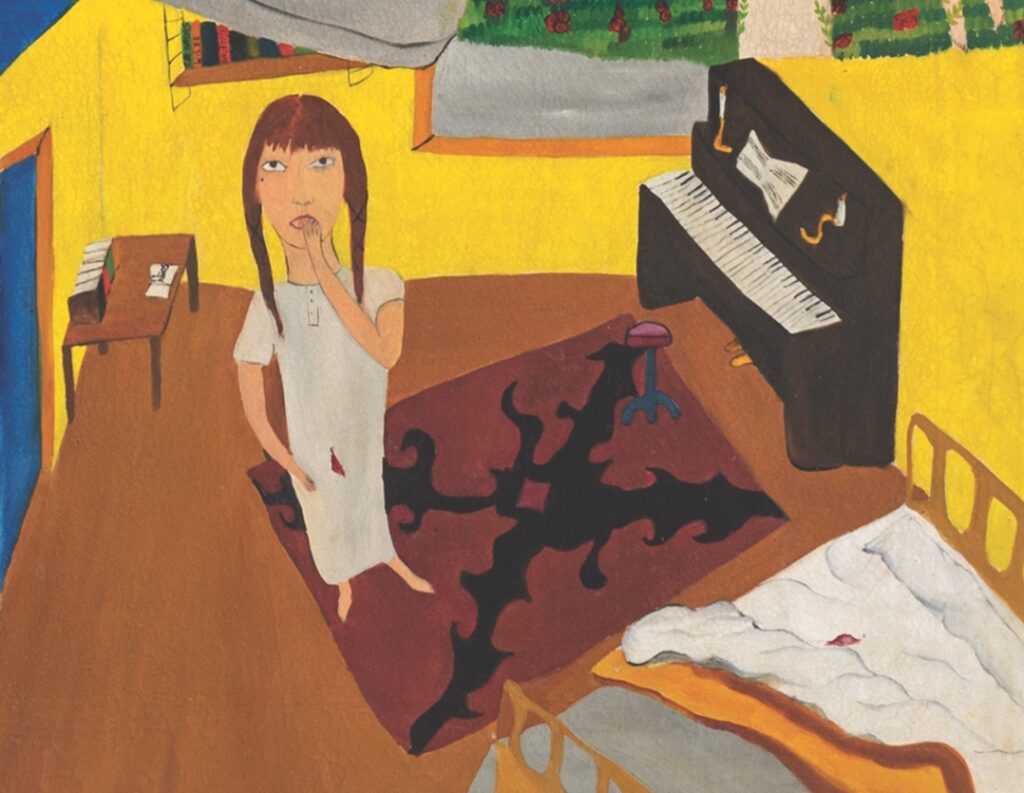

Private collection. Courtesy the artist. © 2024 Cecilia Vicuña/ARS.

I am a photographer (or, I once was). In my discipline, thanks to Roland Barthes’s 1980 treatise Camera Lucida, we refer to the entry point into the photograph as “the punctum.” Though “entry point” isn’t quite right. The punctum, Barthes wrote, is more than a distinct detail; in fact, it can be entirely banal. It is rather “an accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).” What could be a more aching proposition, a more generous way to approach a flat, fixed thing?

Our cover image, Cecilia Vicuña’s painting Janis Joe, is all punctum. Need I even say it? Look at the lower right corner, at the small, triangular bloodstain in the groin of the girl’s white nightgown. It’s like a little vertical rip, a lacuna, a welt, a clue. What has happened here? One hand rests at her hip, drawing our eye to the red spot, and the other in apparent shock at her mouth. We look on, uncertain, moments after the event. Is it her first period, with which she has leapt from bed? Is it the aftermath of a shocking, sudden rape? Slowly, a mirror image emerges, like a twin punctum: a slightly gauzier smudge of blood on the bedsheet. In a bright yellow room, on a gothic rug, next to a piano and upright sheet music, these little red spots feel dangerous. They hold me in ways that I cannot fully explain. A classic trait of the punctum: the inability to be tempered or articulated—we know it only by feeling.

Vicuña made the larger painting from which this vignette is parceled in 1971. It was finished the year after one of its central subjects, Janis Joplin, died at 27. Vicuña herself was only 23 and in the final year of her MFA program at the University of Chile. Two years later, she would be living in exile in the UK following the Pinochet coup. The painting’s other scenes depict whimsy, discovery, worship, lovemaking. Women fly through the sky, sing bottomless, and march in the nude, arm in arm. This episode of a girl in a yellow room is, for me, decidedly darker than the rest, and more foreboding.

What does it foretell? What must it underwrite? The disquiet of the scene is only augmented and made stranger by Vicuña’s painting style, which is itself childlike, with its bold colors, warped perspective, and general sense of wonder and possibility. Here, a child is punctured between the legs. And scarier yet, she is painted as if by the hand of the child herself.