“EVERYONE THINKS THEY know what a love affair is. But what is a love affair really?” Young Kim asks this right off the bat in her debut memoir, A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell, the subject of which is her own personal experience of two love affairs with punk elders: Malcolm McLaren and Richard Hell.

Purchase “A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell”

After a Long Island childhood, college at Yale, and a year of law school at NYU, Young Kim became a student of fashion in (where else?) Paris. There, she began a relationship with the self-styled punk impresario Malcolm McLaren. “Like all great artists, Malcolm was a narcissist,” Kim confesses, surprising no one who knows the first thing about Malcolm McLaren. “The only way he could truly love someone else was if the other person became a part of himself.” Thus, the two of them enjoyed more than a decade of ostensibly true love, until his death in 2010. (They’re partners beyond death, too, in that Kim, his frequent if anonymous collaborator, administers his estate.)

It’s clear in this account that Kim considers McLaren to be the foundational relationship of her life, the loss of which has left her confident that no other man will gain access to the private islands and gracious villas of her emotional landscape. Their love story is placed in stark relief to her brief affair with Richard Hell, of Television and other early CBGBs bands, who conditionally captures her interest but is expressly forbidden access beyond the velvet rope of her interior. Hell, it would seem, is lucky to be invited to her party at all; her VIP section is permanently closed.

We receive A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell from a journalistic remove, like an article in a high-gloss travel magazine. Kim’s language is vivid, detailed and crisp, but most often in reference to the clothes she’s wearing and the names she’s dropping. It bears mentioning that the profusion of name-checked artists and their representatives can be overwhelming. At first I tried to keep up, but I quickly learned to just let it wash over me. She’s not just name-dropping in the context of an anecdote; every so often, she simply rolls the credits. On a single page, one might find some half dozen artists and the cities or institutions where they last encountered them. In one reconstructed conversation, she and Hell lob proper nouns back and forth across the table like ping pong players: Ian Fleming! Ian McEwan! Allen Ginsberg! Sid Vicious! Bob Gruen! William Kunstler! Yale! The Pompidou! Isak Dinesen! Kenya for the holidays! Peter Beard! Carole Bouquet! Paris! The Love Witch! Denver for the weekend!

That’s only page ten.

KIM’S APPLICATION OF cool logic to her lust for Hell, seduction, and sex failed to incite this reader to horniness. To be fair, though, to the degree that she thought about an audience for this book at all, I’m not it. Although I was certainly to be found among the turn-of-the-century East Village wastrels playing “Marquee Moon” on the jukebox in a ripped T-shirt and rummaging around for whatever that generation of artists had found there, the experience did not leave me with much reverence for the remains of that glamorous 1970s punk milieu.

But back to Kim: she idealizes a stylized version of their grit but cannot tolerate unsightliness and is looking into having it permanently removed from her view after “those lonely teen years left their mark on me and taught me to automatically blot out things that I don’t want to see in order to survive—things that I consider ugly.”

In her account of her emotions, Young Kim ranges from amused to bemused. It might seem a too-narrow palette for a sex-based memoir, but there is a certain pleasure—relief, even—in the vicarious experience of her unbothered temperament. Is this the delicious escapism mentioned on the cover blurb by the London Times’s Helen Rumbelow? An escape to a cool place of not really caring very much, putting on and taking off fabulous clothes? If so, I like it. It’s a dissociative kind of pleasure to be immersed in a story that feels like it has so little to do with the rhythms of my own life—almost as transporting as a work of science fiction. Her experience seems so remote as to give me permission to hang my own selfhood on a hook for the duration of the read. Mya Spalter will not be needed in Kim’s world of far-flung openings and fashion shows and always being out to dinner.

An escape to a cool place of not really caring very much, putting on and taking off fabulous clothes? If so, I like it.

Something we learn very quickly about our narrator is that she enjoys being served but bristles whenever a server intrudes by, say, ignoring her when she wants their attention and leering at her when she wants privacy. A waiter mistakes her order of a rare steak for one well done (Sexism, she thinks); another is titillated (she guesses) by her public displays of affection with Mr. Hell. “I was almost certain the staff at the bar had watched. It was very quiet; they needed something to entertain them. I knew people could be nosy and gossipy. . . . It took only one person to notice, and they all talk.” The paranoia of privilege, her imaginative assumption that these working people give a shit about her at all is exquisite in its narcissism. At times, Kim rhapsodizes nostalgically about how much she and Malcolm loved to complain about bad service together, and how he’d especially enjoyed it when she would make scenes on his behalf. True love.

Another thing: Kim is avowedly not a feminist, and she’s not at all kidding about it. Sexism is a waiter getting her order wrong. Systemic gender-based double standards that disadvantage the female and the feminine don’t come up. She likes Ayn Rand a lot and thinks she got a bad rap. She wasn’t freaked out about Trump’s election because she travels so much she figured she’d hardly notice any difference. And maybe it’s petty of me to notice, but at one point she takes the time to mention in print, for posterity, that the special eggs she gets from a farm come by the dozen. Of course eggs come by the dozen—that’s the customary unit in this country, you maniac. I might be blowing it out of proportion, but the egg comment made me think of Lucille Bluth, the wealth-addled matriarch from Arrested Development who famously asked, “How much could a banana cost? Ten dollars?” prompting her son Michael to reply, “You’ve never been to a supermarket, have you?”

Reading A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell, I kept thinking foolishly about Lucille Bluth, but more so about Patsy and Edina from BBC’s Absolutely Fabulous—the glam-chasing, continuously drunk Laurel and Hardy the millennial era deserved. How titillated that duo might be to peek inside this particular set of boudoir doors! Patsy and Edina are celebrity scholars, self-absorbed, fashion obsessed. They are ostentatiously oblivious to anything without a sought-after label and they can’t boil water, but they can tell the season and the designer by the cut of the garment and they keep track of notable people’s affairs as if their lives depend on it because for all practical purposes their lives do depend on it. Once thought, I went about the remainder of my reading with Patsy and Edina in mind as the bullseye Kim might have been shooting her arrows toward—people for whom the approval of a fading generation of rock ‘n’ roll art stars is the pinnacle of cultural cachet.

A STYLISH AND effective writer, Kim expresses herself most deftly through her clothing, which is really impressively described. Everything sounds special and gorgeous and sumptuous. Relatedly, she takes a great creative thrill in giving gifts and has high standards for how they’re reciprocated. Hell often disappoints. Her accounting of their exchanges is so exacting that I’m embarrassed for him. She devises several sexy mail-art assemblages to send him from Nairobi, Paris, and Positano; he replies with tepid texts and warnings not to alarm his girlfriend with suggestive deliveries. She finds his pretense of monogamy quite dull. And while it’s funny to me, her concept of a punk elite—rarified representatives of a subculture that came about as a rejection of institutional elitism (How do you fix your mouth to call someone punk royalty? By the divine right of kings?)—Hell is exactly the kind of toothless old lion she takes a perverse pleasure in indulging. Kim reminds me chillingly of Alma in The Phantom Thread, the woman cast as muse who becomes herself an artist in the medium of her lover’s helplessness, the particular helplessness of the “artistic genius” to attend to things outside of their scope, a narcissistic insensitivity to the world that renders even the most intellectually gifted narcissist kind of stupid. Kim finds this helplessness in men she respects deliciously attractive, delighting in her beloved’s incompetence in a very Munchausen-by-proxy-way that is a little bit romantic, but mostly creepy.

To pick up the book’s original query—what is a love affair?—perhaps it’s characterized by the will to see the love object through a gentling lens. Kim is laser-focused on appearance and stylishness. Hell’s awful attempts at humor, embarrassing lack of phone etiquette, C-minus tailoring, bad manners, lazy racism, and stupid texts don’t perturb her so much as slightly annoy. She recounts a text from Hell:

There was a series of emojis: a peach, an eggplant, and a heart, with the words, “real letter soon.” I felt confused and disappointed. A peach? An eggplant? . . . What kind of message is that? Why was he sending me emojis of produce? I was irked.

But in fact, she relates these instances as an opportunity to marvel at how the things that should bother her about him, don’t. Is that what a love affair is? An occasion to be someone new to yourself? An occasion to investigate your own identity by allowing someone access to your nerves and peeves and being amazed when, by some miracle, they fail to irritate them?

Later, Kim’s interest in Hell is revealed to be an investigation of her own identity. As it turns out, Hell was crucial to the origin story of her late boyfriend Malcolm McLaren. Kim is exploring McLaren’s historical “desire” for Richard Hell and how he consumed Hell’s style and turned it out for profit. She quotes McLaren:

When I saw Richard Hell at CBGB’s, he had on a perfectly groomed, torn, holed T-shirt. His head was down; he never looked up. He sang this song “Blank Generation.” His hair was spiked; he had a kind of nihilistic air… He really was art, and I thought, That’s exactly who I want to sell in my store, that icon!

McLaren had a cannibalistic glee that most people work harder to conceal. He made no bones about his career of consuming people and regurgitating their style for profit in his Kings Road boutique, nor in his boy-band styling of the Sex Pistols. (He’d go on to discover and exploit hip hop in the same way, like some kind of merchant of exotic spices, bringing word of other worlds to the benighted folk of 1980s London.)

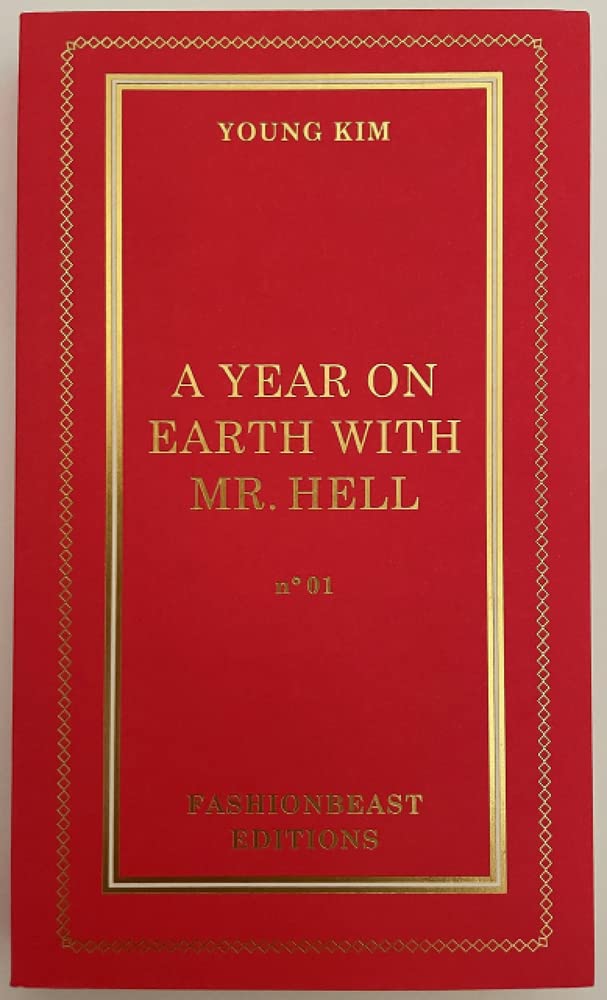

McLaren lived in public. Richard Hell, on the other hand, is famously “private.” He has said in interviews that he left music in the early 1980s (for writing) because he “wasn’t suited to being a quasi-public figure…exposed in those ways.” And yet, Kim only started writing about her relationship with Hell because he asked her to–a bespoke piece of non-fiction erotica. She only continued to write about it because it amused her to do so. And to be honest, she seems to have been much more fulfilled by the writing of the affair than by the affair itself, which is a relatable writerly notion. Kim’s aim in publication seems to be primarily to issue a beautiful art object into the world and, second, to extoll her own well-honed aestheticism, both of which are readily achieved. (The book has the trim-size of a Zagat guide, but in gorgeous Max Factor red with French flaps, lux gold lettering, and blurbs displayed on a strip discreetly wrapping the books lower region, like a dainty vellum towel.) A potential third aim, and this one I’m less certain of, was to piss off Richard Hell a little. He gives her his own memoir as a gift, about which she writes:

What I found remarkable was that half the book was about his sex life. All the different girls he’d slept with, the one who did this, the one who did that, his ploys for luring them to his home when he was bored, how he’d even get off on himself by looking in the mirror.

As Kim labors to detail the unique qualities of her year on earth with Hell she can’t help but make him seem ridiculous, and I honestly can’t tell how much of that, if any, is intentional. She says zero percent, but I’m not buying. He begs her to send nudes with an embarrassing persistence and insensitivity and generally comes across in these pages as sneaky, hapless, and disheveled. Despite her insistence that she finds him adorable, or at the least tolerable for the sake of their special connection, I have my doubts. I don’t doubt that she found Hell and even his behavior attractive—I just doubt that she didn’t have any inkling that sharing someone’s horniest text messages could lead to that person’s embarrassment. Perhaps Hell realized too late what he had unleashed in Kim with his writing assignment. Early on, she recounts the moment when Hell confides that her advanced seduction techniques “made him feel like I was beating him at a game.” She continues: “Well, in a way I was, I had to admit to myself, and I couldn’t help enjoying it.”