BRONISLAVA NIJINSKA (1891-1972) first made her mark as the kid sister and muse of the famous dancer and choreographer Vaslav Nijinsky. Nijinsky, the “God of Dance,” was a troubled genius⎯his original works include some of the first modern ballets–L’Après-midi d’un Faune, The Rite of Spring–whose legendary career was cut short at the age of thirty, when he was institutionalized for schizophrenia. His sister, Bronislava (known by the nickname “Bronia”), also a dancer, was fervently devoted to her brother during his meteoric rise, and has always been understood⎯indeed, in her early years, understood herself⎯as a handmaiden to his vision. The 2017 English-language novel The Chosen Maiden by Canadian scholar Eva Stachniak characterizes the relationship between the dancing siblings as a kind of romance. The title is a reference to Bronia’s role as muse-collaborator in the key solo of the Chosen Maiden, who is assigned to dance herself to death at the conclusion of Vaslav’s The Rite of Spring. We get Nijinska’s version of the same story in her own Early Memoirs, sketched out over decades and edited by her daughter, which keeps a tight and fascinating focus on Vaslav during the period that covers the siblings’ Belarus childhood, abandonment by their dancer-father, and education at the famous school associated with the Maryinsky Theater in St. Petersburg. The memoir ends in the early 1920s, after Vaslav’s brief and controversial stint as a visionary balletmaker for the Ballets Russes.

But after her brother’s institutionalization, Bronia went on to become a master teacher and choreographer in her own right, revered internationally for her ballets Les Noces and Les Biches. Lynn Garafola’s new, encyclopedic La Nijinska is not only a biography of an overlooked choreographer but also a revision of what Garafola calls “the familiar grand narrative of twentieth-century ballet history in the West,” a parade of aesthetic begats which begins with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, the dissolution and diaspora of which produced the multinational ballet companies of the 1930s and ’40s, culminating in the postwar nationalist institutions of Britain’s Royal Ballet and the New York City Ballet. Nijinska is regularly excluded from this parade. In showcasing Nijinska’s theories of dance, her practices in the studio, and her itinerant career as a choreographer without a home base, Garafola presents her as an outsider in the ballet of her time, but one with far-reaching influence. In so doing, Garofala also revises the dance world’s inherited notions of the nature and reach of Modernism in European ballet, which, as understood in Nijinska’s one hundred and sixty original dances, could range from intense religiosity (Holy Etudes) to versions of Ravel’s Bolero where the female soloist dances on a tabletop to the appreciation of a crowd of admirers below. An outstanding example of eye-glazing research in several languages and on several continents, Garafola’s book mounts a painstaking argument for Nijinska as by far the most knowledgeable and creative female ballet choreographer in the twentieth century, and perhaps one of the greatest ballet choreographers of all time.

LA NIJINSKA PICKS up a few years before Early Memoirs leaves off. In our first sighting of Bronia, she is in the “tea-rose lace gown” she wore to her graduation from the Imperial school, a young adult still deeply immersed in her older brother’s influence yet starting to display her “subjectivity,” as she puts it. This biography is about Bronia, untethered from Vaslav. This choice of where to enter the life is both radical and perverse. We don’t grow up with the artist; she pops into view already ripened, rather like one of her characteristic dance effects in which she would appear suddenly airborne, without visible preparation, like a jack-in-the-box. Virginal, she falls under the spell of the magnificent bass opera singer Feodor Chaliapin⎯a practiced (and married) womanizer who did not requite her love with physical consummation but whose imagined being would suffuse her dreams and occupy her deepest yearnings for the rest of her life. If her obsession for the singer was a streak of madness, unlike the mental illnesses of her older brothers (the eldest Nijinsky, Stanislav, was also institutionalized in his twenties), it does not overwhelm the rest of Nijinska’s personality and capacity for rational thought. She is able to compartmentalize her experiences, to relate to her family, to reasonably pursue choreography, coaching, and teaching.

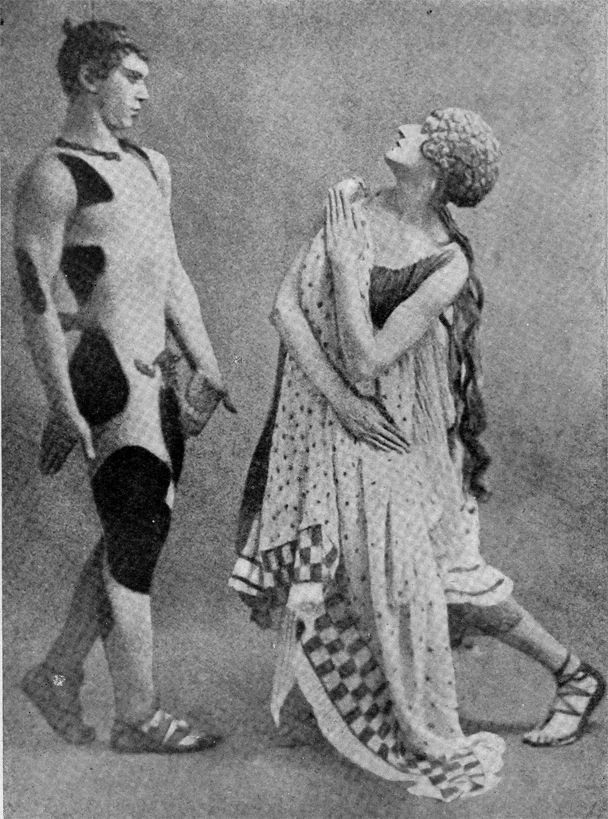

Garafola makes it quite clear that Nijinska did not intend to choreograph entertainments but rather set out to make works of art, each one with its own dialect of classical dancing, its own unique ways of instructing the mind and delighting the soul. She certainly had the skill and, sometimes, the appetite to choreograph story ballets (Baiser de la Fée, Les Cent Baisers, The Swan Princess), and her ballets without librettos could summon dramatic images (such as her staging of Ravel’s La Valse, where nineteenth-century partygoers in a ballroom dance the waltz at one tempo while, in a distant room visible through a doorway, other dancers waltz at another speed). From her years with the Ballets Russes before World War I and then her residence in Kiev, where she established her School of Movement during the early 1920s, Nijinska investigated what many people think of as Modernism in theatrical dance: the one-act storyless or even entirely abstract ballet. This often featured serious or dark themes and choreographic experiments that played fast and loose with line—flexed rather than pointed feet, or gestures that emphasized the elbow. All but a handful of Nijinska’s works have been lost, yet photographs of choreographic moments (the book has several albums of photos, including some in color) confirm an element of unpredictability, of strangeness, in her ballets, where the dancing body also functions as the element of a nonhuman construction. This reader, for one, comes away with the thought that this strangeness, as much as anything, is what makes Nijinska’s Modernism specifically hers—and what constitutes her style’s personal magic. One of her colleagues called it the “Nijinska tang.”

This strangeness is in part related to what some in the dance world perceived as Nijinska’s “ugliness,” which Garafola discusses at length. Nijinska’s unpleasing face and body in the context of ballet were constantly remarked upon. The Russian expatriate critic André Levinson, who despised Nijinska, at least managed to convey in a review something about the energy of her dancing, calling her “a powerful and strange dancer, inebriated with rhythm, who sniffs the music like a drug, breaks and clenches herself in crazy arabesques, vies in speed with the most breathless prestos of the orchestra.” Walter Nouvel, manager of the Ballets Russes, more typically wrote to Diaghilev that Nijinska was “very ugly, especially her mouth and teeth.” Frederick Ashton, enthusiastically describing Nijinska’s class in a letter to Marie Rambert, concluded, “She is a beautiful dancer & a dancer above all her ugliness.” In his book Balletomania, the British critic Arnold Haskell called Nijinska “the only successful woman choreographer in history,” then followed it with “the only ugly dancer to find fame.” The litany of such remarks that Garafola finds necessary to include becomes dismaying (the critiques of Nijinska’s appearance by other women run even longer), but ballet is first and foremost an optical art form. A minor part of the impressions that most dancers make is attributable purely to what they can do—to their native strength and flexibility, their learned skill and musicality. The greater part of a dancer’s impression is attributable to how what they can do looks on the body their mama gave them.

. . . a sacred monster of the theater, over and over Nijinska rebounded from what must have sometimes been discouragement bordering on depression to demonstrate Aesthetic Truth . . .

Still, the ugliness affiliated with Nijinska is more than a recognition of her physical deviation from an expected norm; it is a placeholder for a larger response. Diaghilev, who loved her like a daughter (he gave her away at both of her marriages), spoke of her as “intemperate and anti-social.” The composer Francis Poulenc, who wrote the score for Nijinska’s Les Biches, wrote decades later of her “genius full of unconsciousness that made so much audacity possible.” Garafola speaks of how Nijinska—who could as easily dance male trouser roles (or take on the title role of her brother’s L’Après-midi d’un Faune) as that of a Sylph in Michel Fokine’s Les Sylphides—challenged ballet’s “heteronormativity” in her ease at becoming male or female on stage; added to her masculine-looking features, her practicality in choosing roles regardless of their gender made some people uneasy. She was not only fueled by long-term rage (at her father, at Diaghilev) as well as momentary anger (screaming in class and rehearsal); she was challenging one of the bedrock identities of ballet dancing.

I could understand how she prompted responses that were tremendously unflattering. I met Nijinska in 1970, when she conducted a few rehearsals at Kathleen Crofton’s Ballet Center of Buffalo, where I was a student. She was broad and gimlet-eyed, her voice scraped to the foundation of her larynx by her incessant smoking and barking forth of Russian imperatives, its decibel level raised so as to pierce her own deafness. But she didn’t miss any details of the dancing she had the responsibility to oversee. In this biography, a reader is quickly brought to admire her hands-on stewardship of the choreography, and in Buffalo, I was brought to that admiration as well. In her devotion and knowledge and intuitions, she was charismatic, even though I understood nothing of what she said. Her weirdly cold energy seemed to rise on currents of air from her black silk pajamas, as if some invisible thing were smoking her.

Garafola presents Nijinska as armored in a psychic “carapace.” She would slyly pretend not to understand English so as to diffuse complaints about her I-must-be-right rages in rehearsal (and perhaps to spy on what people were saying about her). Yet, as a sacred monster of the theater, over and over Nijinska rebounded from what must have sometimes been discouragement bordering on depression to demonstrate Aesthetic Truth on those hardy legs, answering the call that only she heard from the art of ballet. If you were a dancer in her class or rehearsal, she could be very hard on you (most especially if you were a male dancer, for whom Vaslav would have been her point of comparison). What Garafola’s book shows to have most predictably provoked her rages was anything that called into question her faith in ballet as “my religion”: mistakes in your dance action, or demonstrations of disrespect, such as choosing to knit or chat or smoke on the sidelines in her rehearsal.

Garafola writes that this book is the “story of a major artist who was also a woman.” Nijinsjka was often hired but rarely rehired, yet I’m not sure I agree with Garafola’s argument that Nijinska’s gender was mainly responsible for keeping her itinerant, moving from company to company without finding a professional home. Nijinska was a perfectionist, and perfectionism is expensive in the theater. She was also on a hardscrabble schedule for years, making decisions that went against the possibility of settling down, and one wonders if being free to pursue her own course better suited her psychic needs. However, the particularities of the woman-artist experience manifest in Nijinska’s angst surrounding her absentee-mother relationship with her children, Irina and Lev. In essence, the children were reared by her mother, Eleonora, and then they reared themselves. Sometimes, Nijinska couldn’t get back to them when they most needed her. Lev, talented in musical composition, wrote to his mother during his teen years that he felt himself going mad. After Lev died in a car accident at age sixteen, Nijinska wrote that for the two years following, she was frozen inside. Irina was critically injured in the same accident but eventually healed and became a ballet dancer and sometime translator for her mother in theaters, as well as a nurse and housekeeper for her mother in the latter’s later years, and, after her mother’s passing, a stager of her works. (In the 1990s, I spent several hours with Irina while reporting on her staging of Les Noces at SUNY Purchase. On the final ting of the score, when a male celebrant at the wedding balances at the top of a human pyramid and opens the fist he’s kept clenched for the entire scene, Irina wept.)

THERE IS, OF course, more to beauty than pleasurable appearance: there is the beauty within. Nijinska was a thinker and a writer of diaries, letters, manifestoes concerning artistry from her years in the USSR, when she hammered out her theory of dance as being made of Movement above all, independent of posing, of literary librettos, and even, she could imagine, of music. Furthermore, she had ideas concerning gesture and the contrapposto use of the upper body while maintaining strict classicism below the waist, a technique that has its legacy in the ballets of Ashton, who studied with her in the 1930s and who loved her. She was a staunch adherent of using the classically schooled body to draw lines, although the kind of line she preferred was assertive, created by sculptural arrangements within the body and among bodies—more of an outline that emphasized mass and pictorial imagery. (Balanchine, whom she hated, also worked for line, but a far more subtle kind, which didn’t require the rescaling of the dancers’ proportions to achieve geometries. Balanchine’s dancers always look like people first and then, as if from a great distance, vehicles for design. For Nijinska, the reverse seems to have obtained.) From Nijinska’s earliest years in the Soviet Union to her last stagings in Buffalo, many dancers professed love for her, corps as well as stars. She was called upon again and again to whip entire companies into shape through her teaching and coaching, and few who underwent her pedagogical genius regretted the experience. Her beauty, for those who embraced her, was her ability—through choreography, teaching, and coaching⎯to make others appear as beautiful as was in them to be.

This biography has so much to offer that it is churlish of me to ponder the question of for whom it is written. Other dance historians, critics, and balletomanes, primarily? Exclusively? As I discovered in trying to finish it in two weeks, it’s not easy to complete. Brilliant research that it represents and labor of love that it is, the tone is not that of a story one sails through for pure pleasure. There are lessons to be learned on every page—and Nijinska-like pronouncements to be aligned from chapter to chapter. It requires headwork and, depending on your familiarity with ballet in Europe between the World Wars, maybe some homework as well. If you haven’t yet read Nijinska’s Early Memoirs, you’ll have to set aside several hours to read that too.

I could envision a graduate seminar on Nijinska based on Garafola’s book, with a final essay assignment to address one question: Knowing what you know about her now, would you hire her for a permanent position in your company? Discuss. However you might answer that, Garafola makes clear that Nijinska, in all her contradictions, cannot remain at the margins of dance history.