Born from a deeply resonant New Yorker essay of the same title published during the 2020 racial violence protests, The Trayvon Generation expands like a blanket of rain across a parched horizon. Following her critically acclaimed memoir, The Light of the World, Pulitzer Prize finalist and bestselling author Elizabeth Alexander turns her gaze toward anti-Black violence. Meditating on the persisting problem of the color line, Alexander alchemizes Black sorrow into a collection of lyrical psalms, reaching, as Black writers and activists have done for decades, toward that tonic which might alleviate Black suffering.

Focused on the plight of her young sons, Alexander examines and grieves the burden that young Black people of their generation have inherited, a burden she evokes with a series of haunting snapshots:

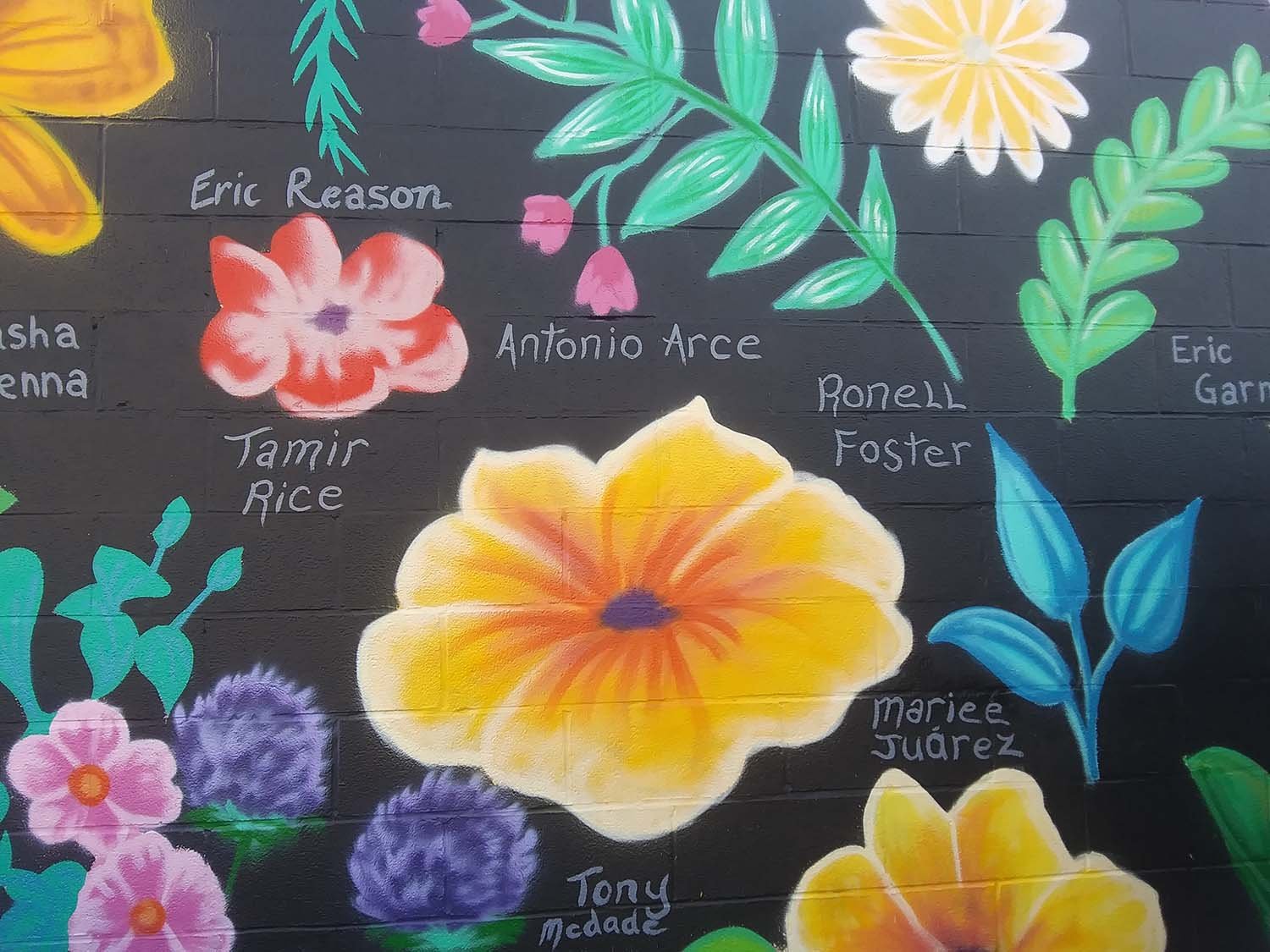

This one was shot in his grandmother’s yard. This one was carrying a bag of Skittles. This one was playing with a toy gun in front of a gazebo. Black girl in bright bikini. Black boy holding cell phone. This one danced like a marionette as he was shot down in a Chicago intersection. The words, the names: Trayvon, Laquan, bikini, gazebo, loosies, Skittles, two seconds, I can’t breathe, traffic stop, dashboard cam, sixteen times. His dead body lay in the street in the August heat for four hours.

This litany confronts the reader with the kind of anti-Black violence that today’s young Black people are forced to constantly negotiate: graphic images that saturate their lives with a novel intensity enabled by social media. Alexander calls these young people, those who have grown up in the past twenty-five years, “the Trayvon Generation.” She explains, “They always knew these stories. These stories formed their world view.”

Alexander uses this book to put words to the heavy sadness that Black youth carry, and to lament the prevalence of mental health issues it perpetuates. “I worry about this generation of young Black people and depression,” she writes. “I believe that this generation is more vulnerable and traumatized than the last,” not only because of the prevalence and visibility of racist violence, but also the “constant display of inequity that has most recently been laid bare in the COVID-19 pandemic, with racial health disparities that are shocking even to those of us inured to our disproportionate suffering.”

Battling against the constant specter of racism, young Black people are stripped of their innocence from an early age. The adultification of Black youth can happen before they leave early adolescence, and often, the farther from childhood a Black person grows, the more they are devalued. Alexander explains the structural utility of this erasure, how “dehumanization precedes violence—in fact, is a precondition for it.” Here, she samples the poem “Your National Anthem” by Clint Smith, which speaks to the experience of losing one’s gentle human spirit: “Today, a black man who was once a black boy / like you got down on one of this knees & laid / his helmet on the grass as this country sang / its ode to the promise it never kept.”

Photo by Charis Caputo.

Intermittent states of grieving and bereavement are a routine part of reality for Black families: “Black communities are full of people wearing T-shirts and hoodies with the faces of young Black people on them whom their communities mourn and remember.” Alexander recalls pausing in New Haven to watch a funeral procession carry away a young Black boy: “I do not know more about this boy, or this story, or how he died. But this is one way Black people live, die, and are mourned.”

The images of violence and death that Alexander shares are necessarily devastating, and they communicate the trauma to which young Black people are subjected on a near-daily basis. She quotes seventeen-year-old Darnella Frazier, who filmed the nine-minute-and-twenty-nine-second video that captured the public lynching of George Floyd. “It was so traumatizing,” Frazier stated through tears to the media. The spectacle of Black murder has become so commonplace that the harm of living in constant, close proximity to it is overlooked.

In the chapter “shock of delayed comprehension,” Alexander shows her reader how, at times, images of white supremacy can hide in plain view, reminding people of color of their perceived inferiority in quieter ways. While some of these images are as stark as the Confederate flag, some persist more subtly—say, in a painting in a conference room at Yale, where Alexander taught for fifteen years and chaired the African American Studies department. She describes her experience of first noticing a young, enslaved child in a painting she had sat under for years: “Once I saw, I could not stop looking at the figure. I could barely conduct business as usual. The Shock of Delayed Comprehension. What did it mean that I had not seen? I asked colleagues, Did you see? Do you see? When did you notice?”

The spectacle of Black murder has become so commonplace that the harm of living in constant, close proximity to it is overlooked.

The experience of awakening to the full force of the racist machine we exist within can be equally jarring. Traces of racist oppression lie coiled within every corner of American society, waiting to strike at any moment. “Racial ideologies are insidious,” Alexander writes. “They instruct in intricate ambient teaching systems. The country is their classroom and everyone is in school, whether they choose to be or not.”

In a world where young Black people are perpetually vulnerable to physical and emotional violence, Alexander searches for a place where they can find relief. A later section of the book explores the options for freedom and negotiates what it means for a Black person to thrive: “How do we measure what that means? What does it mean for our young Black people to be ‘black alive and looking back at you,’ as June Jordan puts it in her poem ‘Who Look at Me’?”

As a mother, Alexander presses her young Black reader to “stand atop the racial mountain, ‘free within ourselves,’” as Langston Hughes wrote. “I pray that those words have meaning for our young people. But our freedom must be seized and reasserted everyday.”

To that end, Alexander takes on a carceral system where prisoners are reduced to slaves. While visiting the Louisiana State Penitentiary, dubbed “Angola” after the former plantation that occupied the territory, Alexander watches as a writing group holds a discussion:

One of the men, who had been in prison since he was a teenager, said, “We dress our ideas in clothes to make the abstract visible.” The phrase arrested me. I thought about my own career as a professor and about the thin line that separated some of the young men . . . If any student of mine spoke those words, I would have leaned closer, been drawn in by the image, and asked to understand more. This life is the only life. There is no liberation in the by-and-by.

In the chapter, “whether the negro sheds tears,” the reader is urged to define Blackness according to the mercy of what it means to be human. As W.E.B Du Bois answered the titular question from a university student conducting a study on the matter, he stated, “We Black people are made mostly of water, blood, and tears . . . We bleed; we shed oceans of tears. Our waters contain our sorrows.”

While the history of Blackness cannot be told without addressing a legacy of grief, brutality, and pain, there is great hope in continual resistance. Alexander writes, “Black flourishing and futurity occur against the odds. But here we are, and yes, we did. Contemporary Black people—if we claim our inheritance—carry not only the hopes and dreams of a generation but also the will and ingenuity to survive.” In this regard, it is essential that Black people hold those who came before in their memories as a beacon for those who have yet to come. “Sometimes the answers are not literal,” Alexander concludes. “Sometimes they take the form of human touch, of the love or encouragement that is transmitted in communities, or the abstract space of possibility that is breath.”

This prose is a gorgeous elegy. Among the sorrow of The Trayvon Generation are also songs of hope and a promise that freedom comes closer with the rising of each new day. As the struggle for racial justice and equality continues, we can all hold this brilliant, pocket-sized book as essential reading to help guide us through the dark.