In 1999 my mother introduced me to John Singer Sargent. I was fifteen, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston was exhibiting the largest retrospective of John Singer Sargent’s works since 1926. Many of Sargent’s most famous paintings were at the MFA retrospective. There was Madame X (1883–84), the scandalous portrait that almost ended his career; Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885–86), a luminous, Edenic picture of two girls lighting lanterns in a garden; and Dr. Pozzi at Home (1881), a striking red painting of a French gynecologist and art collector, his long fingers playing with the ties on his robe—one of Sargent’s most sensual works. I was captivated, not just by Sargent’s glints of light and folds of fabric, but by the subjects themselves, whose temperaments and very humanity felt so vivid on canvas. A lifelong Sargent fan was born.

In our current progressive era, Sargent’s portraits of Gilded Age elite may seem to some dull relics of conspicuous consumption, obsequious depictions of his wealthy clientele. Even in his own lifetime, as his contemporaries were revolutionizing art with impressionism, fauvism, and cubism, Sargent’s work could be dismissed as anachronistic, more Ingres than Matisse (though Picasso, too, took Ingres as an influence). Indeed, Sargent fell out of favor in the mid-twentieth century, as abstraction triumphed over representational art. But to view Sargent in this way is to fail to see him. His brushstrokes and attention to light bear the unmistakable influence of impressionism. He was a great colorist and inventive with composition—his Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), for example, famously draws on Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656).

The 1999 retrospective I saw in Boston (which also showed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Tate in London) heralded Sargent’s comeback. He now seems to be everywhere. One of the last things I did before the pandemic was visit the Morgan Library’s exhibit John Singer Sargent: Portraits in Charcoal. If his technique is underrated, the vividly rendered personalities of his subjects keeps us coming back. Of the outpouring of writing on his work in recent decades, many books have focus on the people he painted, like Deborah Davis’s Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X (2004); Donna M. Lucey’s Sargent’s Women: Four Lives Behind the Canvas (2017); and Julian Barnes’s biography of Dr. Pozzi, The Man in the Red Coat (2019).

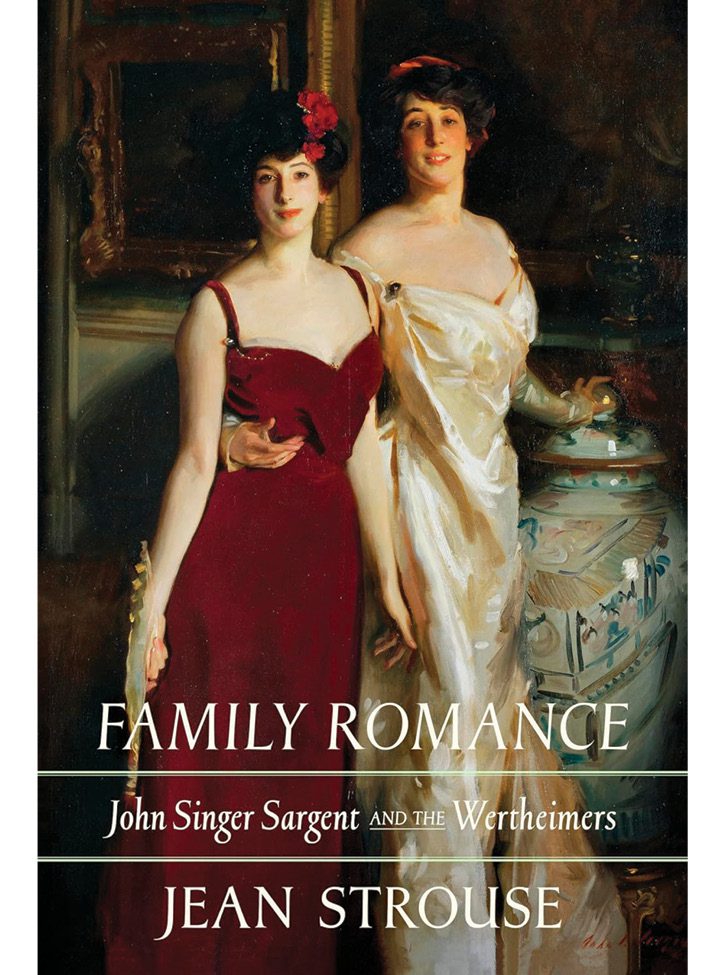

Joining this catalog now is Jean Strouse’s Family Romance: John Singer Sargent and the Wertheimers. Strouse introduces us to the Jewish Wertheimer family of London, who commissioned a series of works from Sargent. Asher Wertheimer, the patriarch, inherited his father’s art dealership, a line of work that brought the family wealth and connections. Asher and his wife, Flora, had ten children who survived past infancy. Sargent painted them all, in twelve portraits, over a decade spanning from 1898 to 1908.

Strouse traces the life history of each Wertheimer that Sargent painted, unearthing new sources. She acquires Sargent’s correspondences with the family at auction, visits the paintings in storage at the Tate, and even digs through archival records from Mussolini-era Italy, where one of the Wertheimer daughters lived as an adult.

She gives the reader as much insight into Sargent as she can, excerpting from his letters and from acquaintances’ accounts of his life and work. When one portrait subject’s family member complains that his depiction has “a little something wrong with the mouth,” Strouse shows us Sargent’s defensiveness at the criticism and how he threads that phrase—a little something wrong with the mouth—through their correspondence for the rest of his life, a long-running inside joke. Sargent and the Wertheimers became friends. We see Sargent acting as an intermediary when Asher and his son, Alfred (pale, serious, and delicately pretty in Sargent’s 1901 painting), fall into an acrimonious dispute about the son’s desire to become an actor. Sargent spent so much time with one of the older daughters, Ena (joyful and flamboyant in both of her Sargent portraits), that her husband suspected she was having an affair with the artist. Upon Ena’s death, her husband searched for proof of their betrayal in the letters she saved from Sargent, only to discover his handwriting indecipherable. The family occasionally considered the nature of Sargent’s interest in the Wertheimer girls in their letters to one another, a question the sisters frequently dismissed with the line: “Don’t be silly, Sargent was only interested in Venetian gondoliers.”

But Family Romance is more than a history of one painter and the family of patrons he often painted—it is a snapshot of Jews in Europe as they move between periods of repression and relative freedom. The Wertheimers’ ancestors left Germany because of restrictive laws limiting Jews from having children and went to a London where Jews were integrating into society, becoming “Anglos of Jewish persuasion.” Yet Sargent’s Wertheimer series, and those of other Jews he painted, occurred as the Dreyfus affair was roiling France, reminding Western Europe’s Jews that they would always be outsiders. In Sargent’s portraits, Strouse writes, the Wertheimers “looked distinctively Jewish . . . dark hair, long faces, significant noses, hooded eyes.”

Family Romance is also a history of Jews in Europe, moving between periods of repression and relative freedom.

Many critics at the time viewed Sargent’s portraits of Jews as exotic curios, reducing them to antisemitic tropes about wealth and greed. Strouse documents this well: One writer described Asher Wertheimer, in his portrait, as “pleasantly engaged in counting golden shekels,” though nothing money related appears in the picture. Another critic declared, “Even Mr. Sargent’s skill has not succeeded in making attractive these over-civilized European Orientals.” A Boston journalist cast suspicion on a different Jewish subject’s motive for commissioning Sargent, writing that the “multi-millionaire Israelite” was trying to “secure social recognition for his family,” as though a Jewish family would not want portraits for the same reason as anyone else.

Strouse’s book is best when it frames the lives of Sargent and the Wertheimers against the rise of fascism in the 1920s and 1930s. Particularly moving is her section on Ruby Wertheimer, one of the younger daughters, whom Sargent painted as a child with a shy gaze and a red bow. Ruby moved to Italy as an adult and became trapped in the country when Mussolini came to power. Strouse recounts her increasingly desperate attempts to escape Italian internment and to acquire medication for her diabetes. She failed and died of her illness. Strouse writes that “this, at least, saved her from the gas chambers.”

On the other hand, the book is limited by a lack of information. Asher Wertheimer’s business archives were lost to history. Strouse lacks the details to create full, vivacious depictions of them as people. Some of the Wertheimer children’s lives are summed up in quick, dry paragraphs, more alive in Sargent’s paintings than they are on the page.

Likewise, Sargent seems more like a cipher than a person. This is not Strouse’s fault: Sargent was famously private. We know very little about his personal or intimate life, with only a few clues, such as the Wertheimers’ comment about Venetian gondoliers, that he might have been attracted to men. In a prolific body of work, he left only three self-portraits, all made on commission. They feel closed off in a way that his portraits of others do not. We can guess, from his close friendships with the Wertheimers, and his willingness to take numerous commissions from Jews, that he did not share the virulent antisemitic views of artists like Degas. Perhaps Sargent, an American expatriate raised in Europe, felt a kinship with Jews as perpetual outsiders, the loneliness of belonging nowhere, a connection Strouse draws as well. Yet his late-career murals for the Boston library featured medieval antisemitic imagery. He complained in his personal correspondence that he was “in hot water with the Jews” but refused to make changes.

To compensate for her subjects’ obscurity, Strouse fills pages of Family Romance with minutiae and tangents. There are endless figures about who bought which art piece for what price. If you have ever longed to read how much the 12th Duke of Hamilton’s estate went for at auction in 1882, you’re in luck. Likewise, parts of the book feel like an avalanche of names we have no attachment to, of people who never appear again. A description of Almina Wertheimer’s portrait veers into a section on a different Almina whom she might have been named for, and continues for three paragraphs, detailing who attended that Almina’s wedding and what her inheritance was, finally telling us that she lived at the estate where Downton Abbey was filmed, before returning to our original Almina. Even so, there are niche joys to be found for the devoted art-history lover in all this trivia, including the details of how Isabella Stewart Gardner purchased two Rembrandts through Asher Wertheimer in 1898—both of which would be stolen in the famous 1990 Gardner Museum theft.

In the book’s final section, Strouse recounts Sargent’s posthumous reputation, from disparagement to redemption, including that 1999 retrospective where I first encountered his work. Three Wertheimer portraits were on display in that exhibit. The family, Strouse writes, has been “almost entirely forgotten.” Family Romance saves the Wertheimers’ history from erasure. But it is Sargent’s portraits that let us transcend time and death, to stand in a light-filled gallery with his subjects: beautiful, Jewish, and alive.