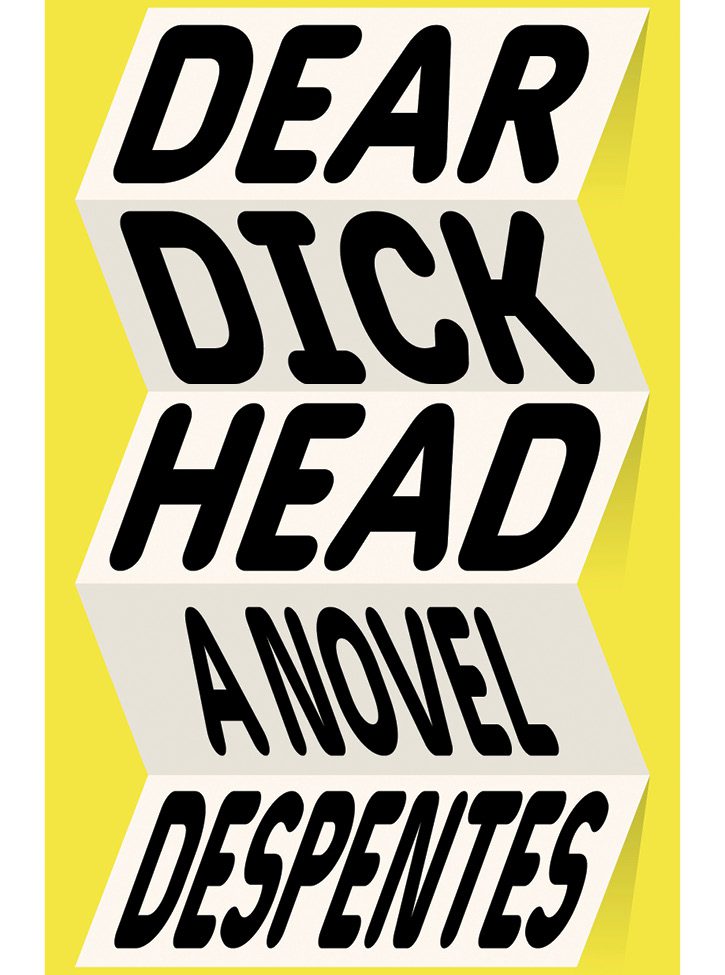

Dear Dickhead is the new novel by one of France’s most celebrated contemporary writers, the so-called punk Virginie Despentes, who came to literary fame as a twenty-three-year-old in 1993 with her first novel Baise-moi (usually translated as “fuck me”). Despentes is a Gen-X French version of Diablo Cody. Since creating Baise-moi, she’s made films and she’s published feminist theory (such as King Kong Theory [Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021]) taught on US campuses, along with writing many, many more novels.

Back to Dear Dickhead.

I really dislike this title. It makes me physically writhe. I don’t mean in a good way. There is just something icky about it, and the revulsion is wrapped up in the irritating fact that this is not the correct translation of the original French title—Cher connard—which somehow rings much better, makes sense, and which I actually like. I can imagine an entire committee pondered and argued over the English translation of the title, landing on Dear Dickhead, but it’s wrong. Worse, it’s just plain unattractive yet not bad enough to be good.

“Dickhead” in French is “tête de noeud,” literally “head of a knot,” or I guess, in British English, “knobhead,” a word I’ve personally never encountered in my somewhat bizarrely sheltered life. I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anyone use the term “dickhead” either. As I wasn’t entirely familiar with it, I did a bit of research both online and with friends. The consensus seemed to be that it’s generally used between men, almost playfully, as an alternative to “idiot.”

The French bilinguals I consulted (including a couple of academics) were unanimous that “asshole” is the accurate translation, thus the correct translation of Cher connard would be “Dear Asshole,” which feels natural. If you were angry at someone, wouldn’t you reflexively use the word “asshole?” “Dickhead” seems an awkward stretch.

“Connard” or “con” is an extremely common derogatory French term. You hear it all the time and there is nothing indecent about it. It’s not an obscene word people will shield from children, unlike the English equivalent of the word it’s derived from, “cunt.” (In case you’re interested, the literal translation of “asshole,” as in anus, is “trou de cul.” Colloquially “connard” just means “jerk” or “asshole.”)

I wondered if the choice of “dickhead” was for alliterative purposes or perhaps to form a connection to Chris Kraus’s cult favorite I Love Dick (Semiotext(e), 1997), which has similar gendered power struggles and, like Dear Dickhead, epistolary aspects. Despentes’s book, though, is completely epistolary as it takes the form of emails exchanged between the dickhead, Oscar Jayack, an until-recently successful writer who has been MeToo’d by a young marketing assistant named Zoe Katana who works at his publishing house, and a fading movie star with the improbable and non-French name (more apt for a porn star) Rebecca Latte. We are never told that Rebecca’s name is not real, though we learn that Oscar’s name (like Despentes’s) is a pseudonym. His real surname is “Jocard.”

The book kicks off when Oscar spots Rebecca at a café (in the trendy Marais district, of course) and posts a nasty and gratuitously misogynistic comment on Instagram: “A tragic metaphor for an era swiftly going straight to hell—this sublime woman who initiated so many teenage boys into the fascinations of feminine seduction at its peak, now a wrinkled toad. Not just old. But fat, scruffy, with repulsive skin with that foul-mouthed female persona. A complete turn-off. Someone told me she’s become an inspiration for young feminists. The fleabag sorority strikes again.” Rebecca notices his post and writes, excoriating him with the salutation, “Dear Dickhead.”

I wondered if the choice of “dickhead” was for alliterative purposes or perhaps to form a connection to Chris Kraus’s cult favorite I Love Dick, which has similar gendered power struggles and epistolary aspects.

And so, with these tropes—over-fifty former sex symbol gone to seed who is duly espoused by feminists—the story unfolds with one more predictable cliché after another. Oscar, for his part, is ashamed and apologetic, and reveals that he partly posted the insults hoping to get noticed. He explains that they grew up together—Rebecca was his older sister’s good friend. After the initial anger gets dialed down, they end up becoming pen pals of sorts, especially as the COVID pandemic hits and there is nothing to do anyway. Both are living on their own. Once in a while, Zoe (the victim/heroine whose hero is Valerie Solanas) pops up via her feminist blog and attacks Oscar. So does Corinne, Oscar’s older sister, who is now a lesbian. But the main story is the epistolary relationship between Oscar and Rebecca, which evolves into something like therapy as they confess and air their problems to each other. (A kind of therapy I can relate to.) Oscar, of course, not only has the MeToo problem of Zoe Katana but a daughter he doesn’t know what to do with, her estranged mother, a current girlfriend who is fed up, and the threat of his substance-abuse problems just barely under control with Narcotics Anonymous (NA). Rebecca, of course, has her own set of predictable problems—she is being passed over for the roles she used to get, she’s getting fat, and she has the same addictions as Oscar (drugs and alcohol).

There is a bit of twistedness and a breaking point in the correspondence when Rebecca reaches out to Zoe and gives her support, which naturally upsets Oscar, and Corinne gets involved as well, along with her attractive girlfriend (prompting Rebecca to wonder if she should become a lesbian). Oscar tries to end the relationship: “I wish I could spew you out of my life like vomit. We’ve been emailing each other for weeks now, you’ve become the person closest to me. And there you are, scheming with my sister behind my back, telling me in that flippant way of yours that you let her flirt with you, then you go visit the girl who’s completely ruined my life.” But, as they are now codependent, Rebecca is moved by his screed and brings him around: “The problem is I’ve gotten used to your emails . . . I’d rather keep writing to you than be bored. Since you’re so keen on honesty, let me give you some: I was genuinely touched when you said I’m the person closest to you right now, and it made me realize that it’s mutual. Let’s face it, we’re getting to be pretty inseparable.” She then reveals that his accounts of the power of NA has led her to surreptitiously join online as well. They bond as recovering addicts.

Overall the narrative of Dear Dickhead is not dissimilar to the kinds of neurotic relationships in Woody Allen films or Lena Dunham’s TV series Girls, but without the fun and humor or the ability to laugh at oneself. Mundanity and clichés don’t mean a story can’t be gripping, but in this case, though I can say the book was enjoyable enough because I live in Paris and it was fun to follow all the references, it didn’t leave a real impression on me or make me want to reread it (something I do all the time)—unlike Despentes’s wonderful Vernon Subutex trilogy (FSG Originals, 2019, 2020, 2021—with the same translator, Frank Wynne).

Vernon Subutex—in particular the first volume, which has rightly caused Despentes to be compared to Balzac and Zola in its colorful and madcap depiction of contemporary Parisian society—dwells on many of the same themes as Dear Dickhead: modern-day Paris and a cast of archetypical (and also somewhat predictable) characters struggling with their neuroses. Both books are peppered with Gen X and French cultural references: Sony Walkmans and VCRs from their youth, the famed Parisian nightclub Les Bains Douches, coveted Levi’s jeans (which were difficult to obtain in France in the 1980s and even early ’90s), Biggie, Burroughs, Prévert, Genet, Basquiat, Hemingway, Wong Kar-Wai and Wachowski movies . . . And neither book has much humor.

However there is a kind of whirlwind magic to Vernon Subutex that Dear Dickhead lacks. Perhaps a crucial difference is that Vernon Subutex has built-in suspense as the eponymous, extremely likable (male, Despentes has pointed out) protagonist has no money, gets evicted, and is searching for places to crash, all the while being the owner of a precious mysterious videotape that unbeknownst to him, several people are on the hunt for. Dear Dickhead, alas, has no such narrative drive, nor are Rebecca and Oscar as compelling as Vernon. I really cared about Vernon and wanted to know more about him, but I feel there is nothing more I need to know about Rebecca and Oscar. It’s not going anywhere I care about. It’s just a bit too familiar and predictable. The familiar can be an intriguing thing as it’s relatable, but sometimes it can be a bit dull. As the Gen X band Radiohead sings: “No alarms and no surprises,” though obviously I wouldn’t go as far as to continue with “get me out of here.”