To make art in a monstrous world, must we embrace the monstrous?

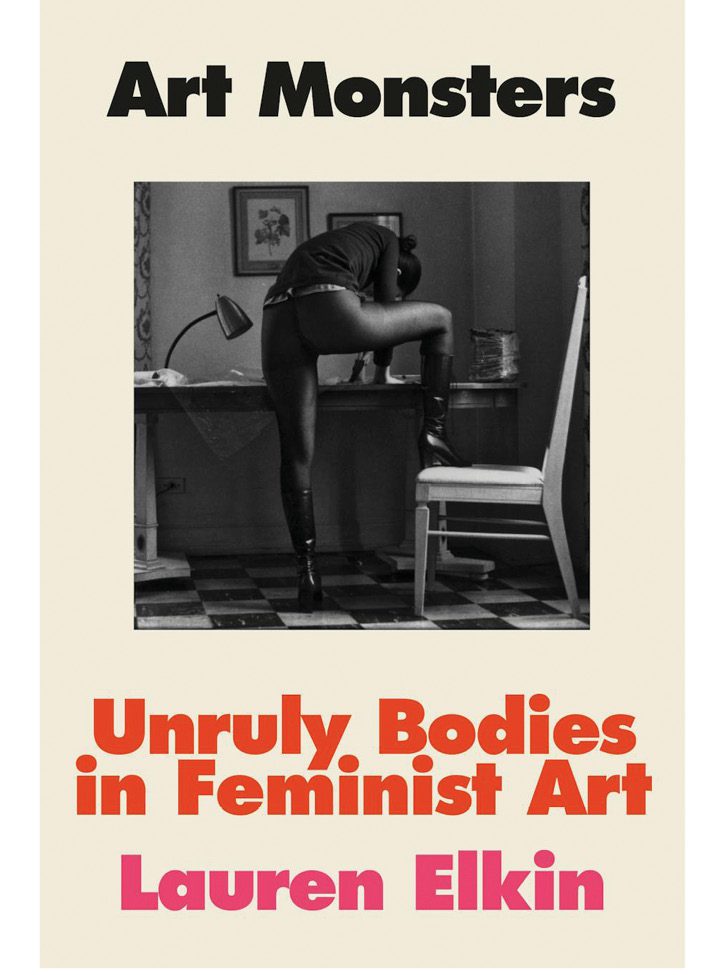

Lauren Elkin’s newest book, Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art, is a meditation on this question. Elkin takes her title from Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel, Dept. of Speculation, in which the narrator, a character named only “the wife,” tells us “My plan was never to get married. I was going to be an art monster instead.”

Offill’s “art monster” is a parody of the archetypal tortured genius, always male, who rejects all other responsibilities in the pursuit of creation. Elkin’s book argues that women can be art monsters, too. For women artists, monstrosity is a reaction against the “Angel in the House,” as Virginia Woolf dubbed the ideal woman, who is “utterly unselfish” and “sacrifice[s] herself daily.” The art monster stands in opposition to marriage, motherhood, domesticity. But Elkin never quite engages with the dichotomy she sets up between artmaking and domestic responsibility. She declares women must “invent our own forms,” yet never explains what those new forms might look like.

Much of the book instead focuses on how the idea of the monstrous intersects with the feminine and feminism, particularly in context of the physical self. Elkin contrasts the female body of classical art, “perfected, clean, polished,” with the grotesque and “abject” body of the living woman, a body that is “not separate from the world but in a state of exchange with it.”

When I read this sentence, I wrote “Dana Schutz” in the margin. Schutz’s art has long interrogated the monstrous and the grotesque. Her sneeze paintings hurl streams and globs of snot at the viewer, exemplifying Elkin’s observation that “the feminist obscene body reaches out and breaks the frame.” Schutz’s figures consume themselves, mouths filled with their own eyeballs, rebooting Goya’s Saturn for our narcissistic age. In Shaving (2010), a figure shaves her pubic hair on a beach, her legs growing out of the mirror, as if to question where the authentic self begins. In Schutz’s work, horror is not always female. Her painting of Michael Jackson’s autopsy—made four years before the singer’s death—intensifies his real-life uncanny-valley image into a greenish Frankenstein’s monster.

To be a feminist art monster, Elkin writes, is to “dare to overwhelm the limits assigned to us, and to invent our own definitions of beauty.” While Elkin never seems to settle on what exactly that means in practice, Schutz’s Jupiter’s Lottery, which opened at David Zwirner in November, is a triumph of monstrosity by nearly every possible definition. The paintings and sculptures on display are immense in both scale and ambition. If we want to celebrate the art monster as a woman who has dedicated her life to her work and mastered it, who asserts her right to take up space in the art world, Schutz fits the bill. Offill’s narrator might be glad to know that Schutz has done it while married and raising three children.

Like Schutz’s earlier works, the pieces here are a delirious mashup of art history, a mad blend of fauvism’s colors, cubism’s geometry, expressionism’s emotional storms. In The Face, a large, disembodied head is held aloft against the sky by figures who appear mostly as stick-like limbs, a composition that evokes Dalí’s 1937 painting Sleep.

In Dear Painter, a woman is held down in bed by a man who paints her lips red. Another man puts a high-heeled slipper on her foot. She holds her own brushes but cannot use them; her unfinished canvas sits on an easel she cannot reach. The subject’s pose and slipper quote Manet’s Olympia, the model for which, Victorine-Louise Meurent, was also a painter, though she is rarely remembered as such. Dear Painter also evokes Frida Kahlo, who often painted from bed. Kahlo’s 1945 self-portrait, Without Hope, depicts the artist trapped in bed while being force-fed.

Schutz’s figures take on distorted and disturbing forms, as in Table Scene, in which a group presents their organs to a greedy dealer. A woman with her head opened and hollowed out has offered her brain; another figure with a red gash across her chest holds out her heart, and a third with empty sockets has left his eyeballs on the table—a satire of the art world, perhaps.

Talking Twin, the most deceptively quiet of these works, shows two identically dressed women sitting side by side on a floral print couch. The delicate features of one woman become rough and garish on the distended head of the monstrous double to her left. It is only on further contemplation that I realized the un-monstrous twin is holding a huge, disembodied tongue across her lap.

The central conflict of the book, Elkin writes, is “the problem of beauty for feminism.”

In Art Monsters, Elkin discusses the fear of many women artists that if their work is too beautiful, it will be dismissed as too feminine. The central conflict of the book, Elkin writes, is “the problem of beauty for feminism.” In response to this conundrum, many of the artists she discusses have turned to the provocative and performative. Elkin looks to the body art of Carolee Schneemann, for example, as well as Lynda Benglis’s famous ad in a 1974 issue of Artforum, in which Benglis posed naked, accessorized by sunglasses and a double-headed dildo. But looking at Jupiter’s Lottery, I found myself wishing that Elkin’s book had engaged more with Dana Schutz’s body of work, which dismantles the idea of feminine art without sacrificing skill or aesthetics. It’s unfortunate that Elkin’s only analysis of Schutz is focused on her already much-discussed painting Open Casket, the depiction of Emmet Till in his coffin that caused a scandal at the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Because Schutz is white, many artists and viewers questioned her right to paint this subject, and the artist Hannah Black circulated a letter demanding that Schutz and the Whitney remove and destroy the painting. (It remained on view throughout the exhibit.)

Jupiter’s Lottery takes its name from one of Aesop’s fables, in which the god sets up a lottery for both mortals and deities. When Minerva wins the prize of wisdom, the humans grow angry, and Jupiter offers them folly as a consolation prize. They leave contented—fools, the story tells us, see themselves as the wisest of all.

It’s hard to consider Jupiter’s Lottery without feeling the weight of Open Casket. The self-satisfied foolishness that the show’s title evokes—is this a rejoinder to those who pilloried her work and called for its destruction? Is it an acknowledgement of the way humility and nuance give way to absolute certainty in today’s discourse? She seems to be agreeing with Yeats here: “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.” In The Arbiters, devious, swollen characters argue at a table. Flies swarm around them, as if their moral decay is made literal. One man is about to strike a glass with an oversized hammer. In The Hill, comical figures paint childish images around an imminent bonfire; one painter gleefully holds a lit match to another’s canvas.

Yet Schutz herself makes no claim on wisdom. In Art Monsters, Elkin writes, of both art and motherhood, “The act of making is the act of unmaking the self . . . Humans can make nothing impervious to time.” It is a final truth that unites both Monster and Angel. Folly may be Schutz’s prize, but she recognizes it with humor. The pictures in this show are absurd, chaotic, sometimes to the point of meaninglessness. It is only the animal subjects—songbirds, macaws, sheep—who look as if they know what is going on. They seem the most human of all. If we seek ourselves in Schutz’s work, we will find only the grotesque: the greedy figures holding dismembered organs, the painters ready to burn their work against an apocalyptic orange sky, the voyeuristic crowds spilling film and money and oil on the ground.