I’m on a live theater kick, so I caught Trophy Boys during its off-Broadway run last summer. The play depicts four male debaters as they decompensate during the seventy-minute (or so) prep session they have before their final match against an all-girls school. The red-hot prompt they have to defend? “Feminism has failed women.” The boys are played by female, queer, trans, and nonbinary actors. Emmanuelle Mattana, the playwright and a lead actor of Trophy Boys, included a note in the playbill that read, in part, “May this show be an invitation; if we can put this on, what can you take off? Gender is a scam but it is also a gift. Drag is radical joy and liberation. The binary hurts us all in different but interconnected ways, as does the systemic effort to deny the existence and rights of queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming citizens . . .” It went on for six paragraphs, but if even more explication was desired, audience members were directed to a QR code for the full program note.

I thought the gender studies 101 preamble was just the insecurity of a young artist—“will people understand my brilliance?”—but it turned out to reflect the show experience and, to me, its problem: rhetoric in lieu of real characters. Despite the tight story capsule, acting talent (including a stand-out Louisa Jacobson, a star of HBO’s The Gilded Age), and the combative prompt, Trophy Boys was less play than Wikipedia article (perhaps titled “Feminist Critiques of Feminism”). Weirder still, the play portrayed all four boys as incel clichés—homophobic but closeted, entitled, porn addled.

I thought about Trophy Boys as I read Did I Leave Feminism?, Jude Ellison S. Doyle’s first book after transitioning. (It is styled as DILF on the cover, a double entendre!) Doyle, celebrated as the writer of the popular blog Tiger Beatdown, discusses how transition changed his (and by extension many trans men’s) relationship to feminism:

I still see so much longing and lostness, confusion and frustration, whenever trans guys talk about feminism. . . . If feminism is no longer for us, are we being punished for “defecting” or “becoming the oppressor?” If it used to be for us—if our bodies and histories are still undeniably marked by the way the world treats people it regards as “women”—then what does it mean to lose feminism’s protection?

These poignant questions emerge in the first few pages, and they are answered quickly. Meanwhile, the title evokes Doyle losing some sense of automatic feminist community and understanding when he transitioned. The reality is that the challenges to his feminist bona fides thrown at Doyle by internet trolls are not evidence of rejection. Feminism itself is a constellation of relationships, beliefs, and actions—not something conferred on anyone by authorities. There is no Roll of the Peerage for women’s liberation. Though he says he was always “becoming a man,” Doyle still has had the experience of being perceived as a woman, and the experience of being treated like a woman, and that lived experience will continue to inform his manhood.

Doyle clarifies that he didn’t leave feminism (answering the inciting question) and that being trans is not some sort of vaccine against misogyny. What follows is absolutely fun, interesting, and even inspiring, but DILF’s antic, ADHD-quality has an unsatisfying shallowness. Doyle riffs, for instance, on the disproportionate number of TERFs in the UK (there rebranded as concerned “mums”), waxes funny and casually erudite (“identity” is “ politically determined suffering”), recounts horrifyingly violent conversations with men (during a stint doing phone sex), reiterates the myth that circumcision kills more than 100 boy babies in the US each year (as evidence of the relative safety of puberty blockers), and Zooms with original male feminist John Stoltenberg (to grill him about Andrea Dworkin’s purported transphobia but concludes “he genuinely wants a feminist future with trans people in it”). The wacky page layout (normal type for the main text flanked by smaller-type sidebar interruptions) tries to make this feed-rendered-in-print cohere.

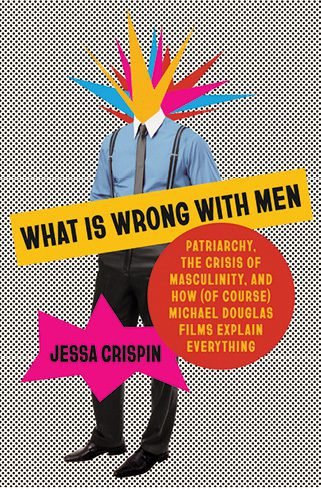

After DILF, I was in the mood for critique that was linear and literary. What if we could analyze the Man Problem through both the gimlet eye of feminism and the squinty eyes of Michael Douglas? We can, thanks to Jessa Crispin’s What Is Wrong with Men (note that the title is not a question—her diagnosis is fully baked). Crispin was also a blogger, but her excellent, now-defunct Bookslut was built for long-form criticism. The book itself is structured in five sections, each with between two and four chapters taking us from the “Mommy Wars” of the 1980s through to the “Rise of the Masculinity Influencer” and incels of current day. Anxiety about “how to be a man,” Crispin argues, is the revved-up engine behind losing Roe v. Wade,ICE raids, mass shooters, and pretty much all of my nightmares.

In a non-gimmicky way, Crispin positions Michael Douglas as an actual first-generation après-feminism man (dad Kirk Douglas being the last of the old school). But her subject is not Michael Douglas the person but Douglas the performer, an avatar that she frames in conversation with the radical shifts wrought by second wave feminism. Dan Gallagher, the “Did I do that?” husband in Fatal Attraction (1987), is baffled that his one-night stand (Glenn Close) insists, “I won’t be ignored.” Doesn’t she realize he’s married and has a lot to lose? Why is she doing this to him? Tom Sanders is falsely accused of sexual harassment by Demi Moore (the real harasser!) in Disclosure (1994)—why can’t people see that he’s the victim? There is also Oliver Rose in The War of the Roses (1989): a workaholic caught in a fatally petty divorce once his wife admits she’s unfulfilled and then starts a catering business to achieve financial

independence.

Douglas’s resentful characters are usually married, and like DILF, What Is Wrong with Men has a lot to say about marriage as a free labor scheme masquerading as mutual support. While patriarchy in general has taken a hit from feminism, marriage, Crispin writes, “retained its patriarchal nature, and therefore was structured in such a way as to benefit primarily the man, often at the expense of the woman.” Between 1960 and 1980, the divorce rate more than doubled. While “women report a boost of happiness and a decrease in stress levels when they divorce their male partners,” she says, generations of de facto matriarchal family life left some boys getting life lessons from “strong” father figures like Jordan Peterson and Donald Trump.

Starting with Wall Street’s(1987) Gordon Gekko, Crispin zeros in on the villain that, in her view, makes patriarchal privilege look tame: good old American greed. Since 1970s women’s liberation, pillars of institutional patriarchy have been falling, yet what replaced it was “sneaky and amorphous.” It looked “like a meritocracy,” but that’s not how it worked. “Masculinity has always been about competition, war games, and who dies with the most toys,” she writes. But the patriarchy, understood as a “system of institutions rituals, and roles” like soccer coach, deacon, and family man encouraged “hard work, delayed gratification, and public service.” With the erosion of patriarchy, men were severed from all that gave them a sense of meaning or power. Left to seek purpose in the “feminine” realms of domestic or personal life (a no-go), the only space left for masculine success is acquiring wealth. Only currency still has currency. Crispin’s diagnosis of terminal avarice is dramatized via Michael Douglas films, but her analysis is informed by dozens and dozens of books, including Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House (1887), Casino Capitalism by Susan Strange (1986), and Donovan X. Ramsey’s When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era (2023).

“I don’t want to live in Michael Douglas’s world. I’ve done too much of that as it is! And not even he seems all that happy there,” Crispin writes to close the book. “What I want, instead, out of love, is to invite him into mine.” This thought of men entering “my” world stuck with me. In a way, Doyle is arguing for men to walk through that door, too, starting with trans men. Men are flailing. The women’s movement was supposed to liberate women to take themselves and their talents seriously and liberate men from being hard-charging and emotionally stunted. The second wave created “narrative structures and the intellectual framework with which to understand [women’s] own unhappiness in contemporary society,” Crispin writes, “especially as it involved domestic life.” Escaping the sandbox, women entered public life in droves.

That plus intractable sexism resulted in women’s double competency—we do free domestic labor and paid labor both—but what did women’s liberation free men to partake in? The domestic and private sector, “something they had been accustomed to denigrating.” In other words, men may be miserable, but at least they aren’t women.

This is not altogether new stuff. In Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Male, all the way back in 1999, Susan Faludi asked why men, demonstrably unhappy, didn’t take a page from the women’s liberation movement and evolve. “One wonders,” Crispin writes in a work of someone quite past wondering, “if the inability of American masculinity to admit its failings and its state of decline is, in some part, a fear of being held accountable.” The masculinity crisis continues. It’s a riddle wrapped in ignorance and, as usual, women are on cleanup crew.