I was on my daily journey to my summer internship when I heard a familiar tune from high school by the Massachusetts queercore band DUMP HIM. “Dykes to Watch Out For” (the title track) was almost spookily aligned with my daily life this summer. Take this lyric: “Your home is now a monument / How radical just to document you exist.” I was interning at Bay Area Lesbian Archives (BALA), located in the former home of illustrious activist Elana Dykewomon—the Sinister Wisdom editor, prolific writer, and San Francisco Dyke March organizer whose house is now literally a monument to lesbian life and documenting our existence.

I learned about BALA from a list of approved praxis internships at my college, Smith. The archive itself was the brainchild of curator, photographer, and filmmaker Lenn Keller. In 2014 Keller sounded the alarm about the shockingly slight degree to which lesbian history was being preserved. Lesbians, as outsiders, may have always been among the leaders in women’s liberation, but this outsider status also meant a lack of resources to document and archive their rad lives for future feminists to learn from. A core group gathered with Lenn Keller to collect oral histories, artifacts (like Cris Williamson LPs or Dyke March regalia), and documents such as flyers for conferences and concerts and rare books and journals—all gathered from local lesbians who were active in the 1970s and 1980s.

Lenn Keller died in 2020 at the age of sixty-nine, having dedicated the last six years of her life to the archive. Elana Dykewomon passed in 2022 at the age of seventy-two, twenty minutes before the premiere of her play, called How to Let Your Lover Die, about her partner’s death six years earlier. Dykewomon bequeathed BALA her house, the collection was unified in a physical space for the first time, and archive enthusiasts like me were invited to process the donations. That is how I wound up spending the summer working with supervisor Sharon De La Peña Davenport (a poet, archivist, and Smithie—always quick to tell everyone her age: “Seventy-

nine, soon to be eighty!”), an intern from Mount Holyoke, and a rotating cast of dedicated local volunteers.

The world that I found myself dropped into at BALA was unlike anything I’d experienced. Growing up in Dallas, the gayborhood I knew was Oak Lawn. A freewheeling hub for Dallas’s queer community in the 1960s due to cheap rent (thus the presence of the city’s counterculture), during my lifetime, Oak Lawn was populated by every affluent gay male professional in Dallas. Oak Lawn never felt like a place for me, even if the men there were technically part of my queer community. I’d read Malinda Lo’s Last Night at the Telegraph Club and Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl, so I had an idea of the Bay Area as a magical queer city—and it was.

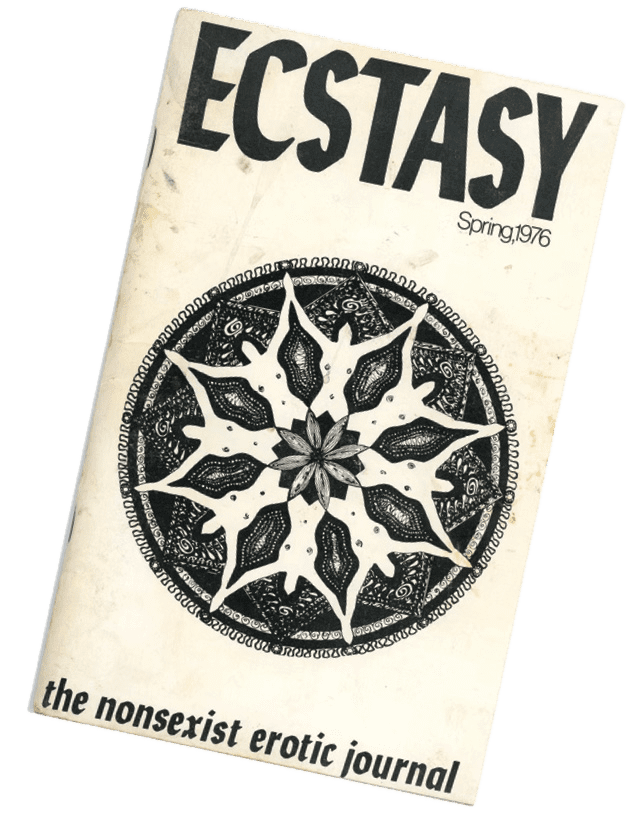

At BALA, I helped process donations, watched films made by Lenn Keller, and listened to Lesbian Concentrate on vinyl from Olivia Records in a reading room filled floor to ceiling with lesbian books. I nailed up a vintage “Brick Hut Café”1 banner, debated the exact mission of BALA, gossiped over archival sleeves with people of all ages. Handling the books and periodicals of feminist and lesbian culture pointed me to a treasure map of long-gone bookstores and music festivals I’d never heard of that had functioned as organizing spaces and safe havens for lesbians and feminists. I began to see how the radical feminist journals and periodicals of the late 1960s through the early 1990s—Radiance, Paid My Dues, Tradeswomen—had made grassroots feminism possible, because it connected women who would not have found each other any other way. Though most of these journals are gone, community-run archives like BALA continue to serve as a third space in a way that a ritzy gayborhood just can’t.

Archiving and library work may not sound like a fierce-enough match for the fascist resurgence we are facing. But as we worked with scraped-together funding in the home of a now-passed lesbian activist to document the lives of other lesbians, I felt how BALA’s existence was its own political act. By forming a community memory center and meeting space, the archive links the lesbian elders’ strength to that of the people who help BALA run, like me. Preserving queer history is important, but experiencing the community, love, and joy of that lesbian house in Oakland was unforgettable.

Back in Northampton, I can sit in my dorm room listening to “Dykes to Watch Out For” and recall BALA’s back garden with persimmon trees everywhere, Sharon’s tin of hand-rolled cigarettes, and the beautiful shelves stacked with evidence of people’s lives (shirts from protests, love letters between girlfriends, records of meetings that changed the world). I know those shelves are protected from the people who don’t see their magic (or do and want it erased). I can remember the letters I read and the feeling of seeing myself in them, in some future-y past. When DUMP HIM sings, “I check the records, dating back to some other time / I look for myself, I see it in your photographs,” I sing along.

- The Brick Hut was a lesbian feminist café that ran from 1975 to 1996 in Berkeley. Founded by Sharon

De La Peña Davenport and Joan Antonuccio, it doubled as a gathering and organizing space for the lesbian community and various activist groups. ↩︎